- Home

- Magazines

-

Newsletters

- 19 July 2024

- 12 July 2024

- 5 July 2024

- 28 June 2024

- 14 June 2024

- 7 June 2024

- 31 May 2024

- 24 May 2024

- 17 May 2024

- 10 May 2024

- 3 May 2024

- 26 April 2024

- 19 April 2024

- 12 April 2024

- 22 March 2024

- 15 March 2024

- 8 March 2024

- 1 March 2024

- 23 February 2024

- 16 February 2024

- 9 February 2024

- 26 January 2024

- 19 January 2024

- 12 January 2024

- 22 December 2023

- 1 December 2023

- 24 November 2023

- 10 November 2023

- 3 November 2023

- 27 October 2023

- 20 October 2023

- 13 October 2023

- 6 October 2023

- 29 September 2023

- 22 September 2023

- 15 September 2023

- 8 September 2023

- 25 August 2023

- 18 August 2023

- 11 August 2023

- 4 August 2023

- 28 July 2023

- 21 July 2023

- 14 July 2023

- 7 July 2023

- 30 June 2023

- 23 June 2023

- 15 June 2023

- 2 June 2023

- 26 May 2023

- 19 May 2023

- 12 May 2023

- 5 May 2023

- 28 April 2023

- 21 April 2023

- 14 April 2023

- 6 April 2023

- 31 March 2023

- 24 March 2023

- 17 March 2023

- 10 March 2023

- 3 March 2023

- 24 February 2023

- 17 February 2023

- 10 February 2023

- 3 February 2023

- 27 January 2023

- 13 January 2023

- 22 December 2022

- 15 December 2022

- 9 December 2022

- 2 December 2022

- 25 November 2022

- 18 November 2022

- 11 November 2022

- 4 November 2022

- Advertising

- Subscribe

- Articles

-

Galleries

- AOSH Firexpo 2024

- Midvaal Fit to Fight Fire 2024

- WoF KNP 2023 Gallery

- TFA 2023 Gallery

- DMISA Conference 2023

- ETS 2023 Gallery

- Drager Fire Combat and Rescue Challenge 2023

- AOSH Firexpo 2023

- Midvaal Fit to Fight Fire

- WC IFFD 2023

- NMU 13th Fire Management Symposium 2022

- JOIFF Africa Conference 2022

- ETS 2022 Gallery

- TFA 2022 Gallery

- IFFD 2018

- SAESI

- TFA

- WRC 2018

- WRC 2019

- A-OSH/Securex

- IFE AGM 2019

- ETS Ind Fire Comp Nov 2019

- ETS Challenge 2021

- Drager launch

- Drager Fire Combat and Rescue Challenge 2022

- TFA

- Contact

- Home

- Magazines

-

Newsletters

- 19 July 2024

- 12 July 2024

- 5 July 2024

- 28 June 2024

- 14 June 2024

- 7 June 2024

- 31 May 2024

- 24 May 2024

- 17 May 2024

- 10 May 2024

- 3 May 2024

- 26 April 2024

- 19 April 2024

- 12 April 2024

- 22 March 2024

- 15 March 2024

- 8 March 2024

- 1 March 2024

- 23 February 2024

- 16 February 2024

- 9 February 2024

- 26 January 2024

- 19 January 2024

- 12 January 2024

- 22 December 2023

- 1 December 2023

- 24 November 2023

- 10 November 2023

- 3 November 2023

- 27 October 2023

- 20 October 2023

- 13 October 2023

- 6 October 2023

- 29 September 2023

- 22 September 2023

- 15 September 2023

- 8 September 2023

- 25 August 2023

- 18 August 2023

- 11 August 2023

- 4 August 2023

- 28 July 2023

- 21 July 2023

- 14 July 2023

- 7 July 2023

- 30 June 2023

- 23 June 2023

- 15 June 2023

- 2 June 2023

- 26 May 2023

- 19 May 2023

- 12 May 2023

- 5 May 2023

- 28 April 2023

- 21 April 2023

- 14 April 2023

- 6 April 2023

- 31 March 2023

- 24 March 2023

- 17 March 2023

- 10 March 2023

- 3 March 2023

- 24 February 2023

- 17 February 2023

- 10 February 2023

- 3 February 2023

- 27 January 2023

- 13 January 2023

- 22 December 2022

- 15 December 2022

- 9 December 2022

- 2 December 2022

- 25 November 2022

- 18 November 2022

- 11 November 2022

- 4 November 2022

- Advertising

- Subscribe

- Articles

-

Galleries

- AOSH Firexpo 2024

- Midvaal Fit to Fight Fire 2024

- WoF KNP 2023 Gallery

- TFA 2023 Gallery

- DMISA Conference 2023

- ETS 2023 Gallery

- Drager Fire Combat and Rescue Challenge 2023

- AOSH Firexpo 2023

- Midvaal Fit to Fight Fire

- WC IFFD 2023

- NMU 13th Fire Management Symposium 2022

- JOIFF Africa Conference 2022

- ETS 2022 Gallery

- TFA 2022 Gallery

- IFFD 2018

- SAESI

- TFA

- WRC 2018

- WRC 2019

- A-OSH/Securex

- IFE AGM 2019

- ETS Ind Fire Comp Nov 2019

- ETS Challenge 2021

- Drager launch

- Drager Fire Combat and Rescue Challenge 2022

- TFA

- Contact

|

10 November 2023

|

Featured FRI Magazine article: In the global climate change debate – is fire green? by Lynne A Trollope and Dr Winston SW Trollope, research and development, Working on Fire International (FRI Vol 1 no 8)

This week’s featured Fire and Rescue International magazine article is: In the global climate change debate – is fire green? written by Lynne A Trollope and Dr Winston SW Trollope, research and development, Working on Fire International (FRI Vol 1 no 8). We will be sharing more technical/research/tactical articles from Fire and Rescue International magazine on a weekly basis with our readers to assist in technology transfer. This will hopefully create an increased awareness, providing you with hands-on advice and guidance. All our magazines are available free of charge in PDF format on our website and online at ISSUU. We also provide all technical articles as a free download in our article archive on our website.

In the global climate change debate – is fire green?

By Lynne A Trollope and Dr Winston SW Trollope, research and development, Working on Fire International

As practicing fire ecologists and managers the question that arises in the debate on global climatic change is whether fire is green or not ie is it contributing to global warming? This is a particularly pertinent question as prescribed burning is widely recognised as an essential practice in the management of African grassland and savanna ecosystems. In recent years, devastating mega fires have been occurring on a more regular basis in areas like Australia, North America, the European Mediterranean basin and even during 1999 in South Africa. Therefore, as an organisation, the local and international components of Working On Fire, needed to address this question and take a position on whether fire is green or not. However, in investigating this topic, it is first necessary to obtain an overall understanding of global warming and its impact on global climate change before focussing on the possible contribution of fire to this major challenge facing the world in the 21st Century.

Background to global warming

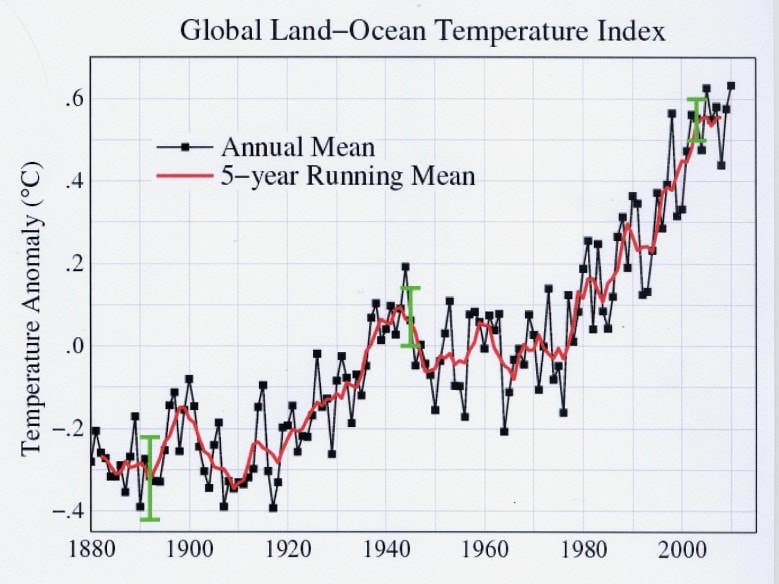

In 1975, Wallace Broecker, latterly based at the University of Columbia, was the first scientist to predict global warming due to increased levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere. He had been involved in carbon dating ice cores from Greenland and sediment cores from the Atlantic sea floor which provided records of climates past. From data gathered thus far, he realised that climate is not stable. As he so succinctly put it “climate is a tetchy beast subject to large and abrupt mood swings.” At the time, Charles David Keeling was a young scientist who was hired to document the first reliable measurements of CO2 on the north slope of Mona Loa in Hawaii and became famous for the “Keeling Curve” of CO2 measurements. Simple physics and Keeling’s data made it clear that global temperatures would rise at a rate parallel to that of atmospheric CO2, and would continue to do so in the future, unless the problem was addressed (see figure 1). Broecker’s biggest contribution to science is the fundamental idea that climate does not just change smoothly and continuously but rather that it also shifts abruptly between discreet states ie it has tipping points. He reasoned that the massive emissions of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere seemed like a good way of pushing climate towards a series of tipping points. Burning fossil fuels is not bad; what is bad though, is dumping the gaseous waste into the atmosphere (Broecker and Kunzig, 2008).

In the global climate change debate – is fire green?

By Lynne A Trollope and Dr Winston SW Trollope, research and development, Working on Fire International

As practicing fire ecologists and managers the question that arises in the debate on global climatic change is whether fire is green or not ie is it contributing to global warming? This is a particularly pertinent question as prescribed burning is widely recognised as an essential practice in the management of African grassland and savanna ecosystems. In recent years, devastating mega fires have been occurring on a more regular basis in areas like Australia, North America, the European Mediterranean basin and even during 1999 in South Africa. Therefore, as an organisation, the local and international components of Working On Fire, needed to address this question and take a position on whether fire is green or not. However, in investigating this topic, it is first necessary to obtain an overall understanding of global warming and its impact on global climate change before focussing on the possible contribution of fire to this major challenge facing the world in the 21st Century.

Background to global warming

In 1975, Wallace Broecker, latterly based at the University of Columbia, was the first scientist to predict global warming due to increased levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere. He had been involved in carbon dating ice cores from Greenland and sediment cores from the Atlantic sea floor which provided records of climates past. From data gathered thus far, he realised that climate is not stable. As he so succinctly put it “climate is a tetchy beast subject to large and abrupt mood swings.” At the time, Charles David Keeling was a young scientist who was hired to document the first reliable measurements of CO2 on the north slope of Mona Loa in Hawaii and became famous for the “Keeling Curve” of CO2 measurements. Simple physics and Keeling’s data made it clear that global temperatures would rise at a rate parallel to that of atmospheric CO2, and would continue to do so in the future, unless the problem was addressed (see figure 1). Broecker’s biggest contribution to science is the fundamental idea that climate does not just change smoothly and continuously but rather that it also shifts abruptly between discreet states ie it has tipping points. He reasoned that the massive emissions of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere seemed like a good way of pushing climate towards a series of tipping points. Burning fossil fuels is not bad; what is bad though, is dumping the gaseous waste into the atmosphere (Broecker and Kunzig, 2008).

Figure 1: The Keeling curve of rising temperature and CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere

At the time that the global warming issue was coming to the fore, the climate change sceptics complained that the same scientists had been crying wolf about global cooling as there had been a thirty year cooling trend in climate data. Broecker explained that the science then was not the same and neither were the scientists, but great strides and developments had been achieved in global climate monitoring leading to a greater understanding of the incredible complexity of the subject.

Possible causes of climate change

The possible causes of global warming and the resultant climate change are:

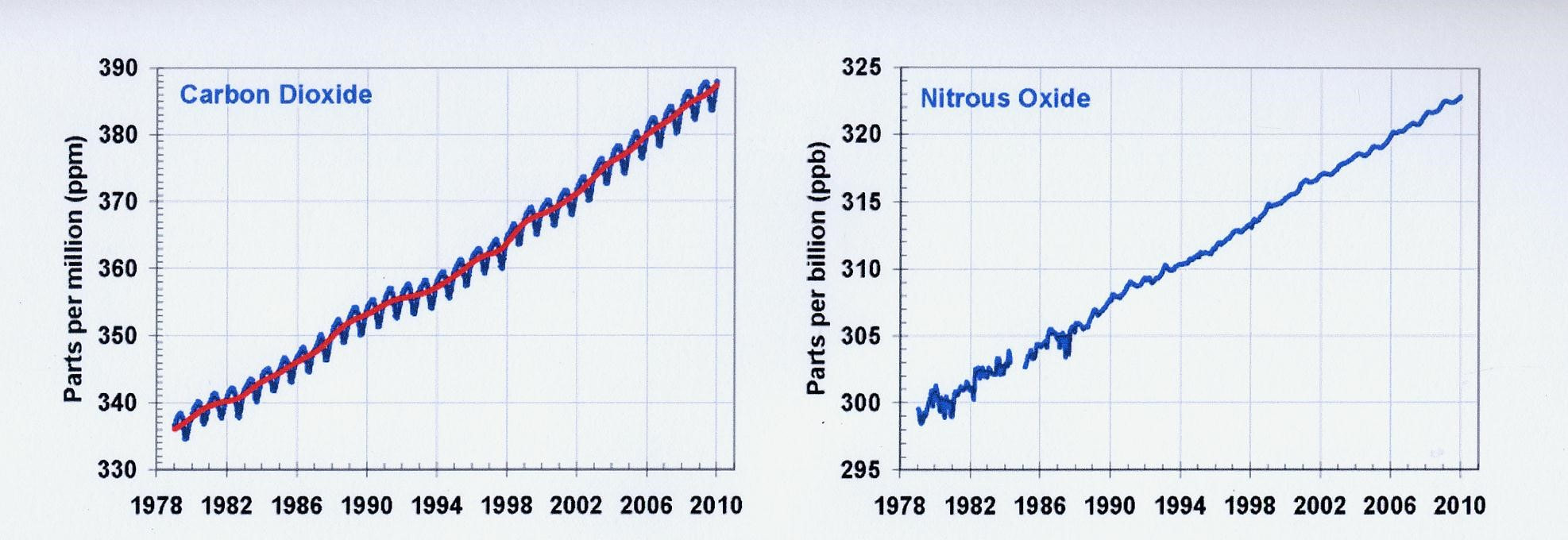

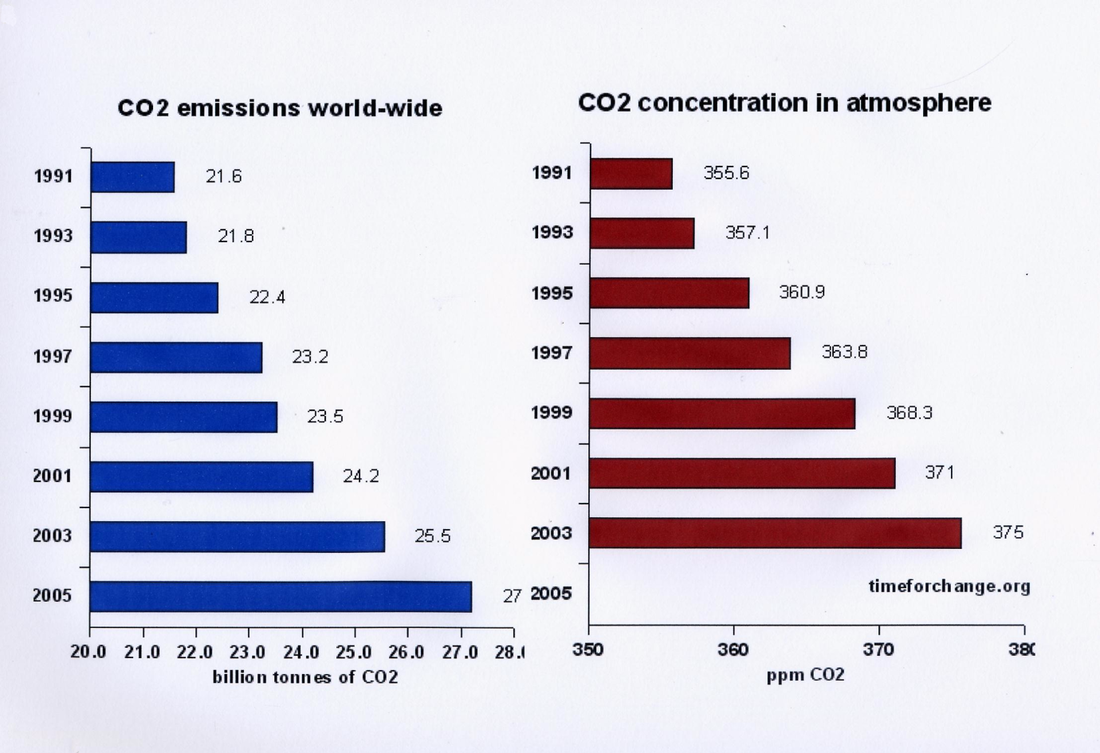

Historical trends in the above gases are illustrated in figure 2.

At the time that the global warming issue was coming to the fore, the climate change sceptics complained that the same scientists had been crying wolf about global cooling as there had been a thirty year cooling trend in climate data. Broecker explained that the science then was not the same and neither were the scientists, but great strides and developments had been achieved in global climate monitoring leading to a greater understanding of the incredible complexity of the subject.

Possible causes of climate change

The possible causes of global warming and the resultant climate change are:

- Elevated levels of CO2 due to human activities preventing the reflection of infra-red radiation back into space, ie the greenhouse effect.

- Methane (CH4) which has a twenty five times greater effect on global warming than CO2 but which is currently present in smaller quantities. The sources of methane are increased numbers of livestock, burning natural gas and emissions from garbage in land-fills.

- Nitrous oxide (N2O), a powerful greenhouse gas that has increased 15% since 1750 and which has a 310 times greater effect than CO2. It is a by-product of plastics and fertiliser manufacture and use (World Resources Institute (WRI) Org, 2011).

Historical trends in the above gases are illustrated in figure 2.

Figure 2: Trends in rising greenhouse gases from 1978 to 2010 (WRI Org, 2011).

In the complex equation of climate change the contributions of some of the different elements in the atmosphere to the greenhouse effect are as follows:

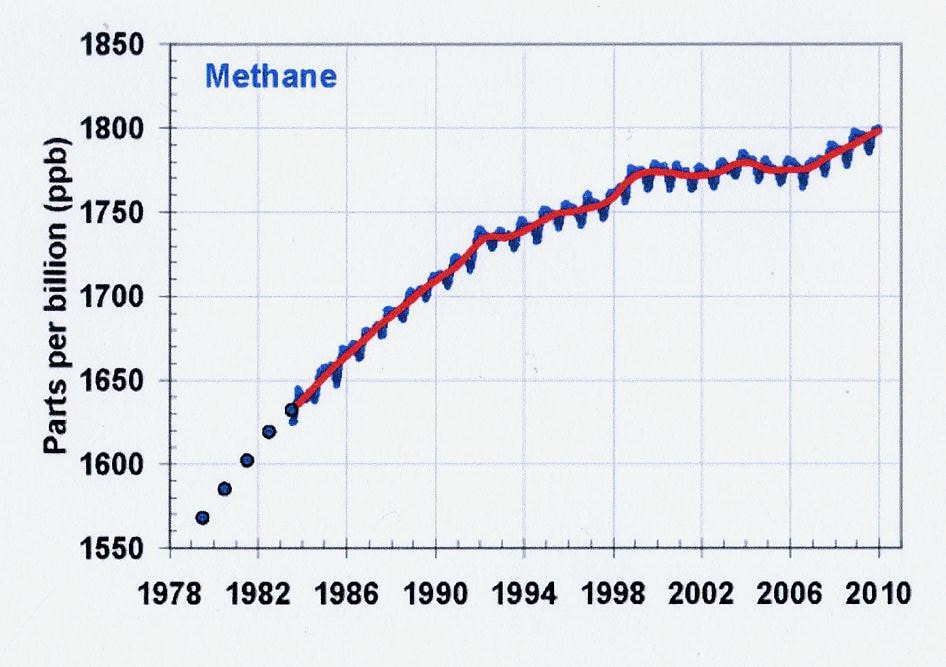

However CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere remain the major cause for concern. Global emissions and concentrations are presented in figure 3.

In the complex equation of climate change the contributions of some of the different elements in the atmosphere to the greenhouse effect are as follows:

- Water vapour has the greatest effect, making a 36 to 72% contribution by trapping the infra-red radiation. Heating of the oceans caused by rising global temperatures results in greater evaporation and increased cloud cover and therefore global warming.

- CO2 follows with nine to 26% contribution.

- Whereas methane, said to be 25 times more effective in influencing climate change than CO2, is next with a four to nine percent effect.

- Finally ozone also plays a role with a three to seven percent impact.

However CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere remain the major cause for concern. Global emissions and concentrations are presented in figure 3.

Figure 3: Global emissions and concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere (WRI Org, 2011)

Examples of the effects of global climate change

In spite of the scepticism about climate change like Bjorn Lomborg of “The Sceptical Environmentalist” fame, the general consensus of the main stream scientists involved in the global warming debate is that it is a major challenge for the world in the 21st century. Global temperatures are predicted by these scientists to rise 1,8 – 6,0oC by 2100. Mark Lynas, activist, journalist and author of the book Six Degrees, paints a chilling degree-by-degree scenario of the devastation likely to occur and issued a global warning – “Act now or risk mass extinction!” (Lynas, 2008). For many there is no doubt that global warming is occurring. This is borne out by the melting of glaciers the world over, rising sea levels threatening the Atoll nations and the disappearing ice caps both in the Arctic and Antarctic peninsulas. The plight of the polar bears with the melting pack ice highlighted the problem to the general public (Collins, 2007).

Closer to home, the major increase in bush encroachment in southern Africa, has been attributed to increased CO2 levels in the last century (Buitenwerf et al, 2011). This is supported by the hypothesis that C3 plants (trees and shrubs) are favoured by increased levels of CO2 compared to grasses which are C4 plants (C3 and C4 refer to the photosynthetic pathways involved in the metabolism of these plants). In this regard, Professor Tim Hofmann at the University of Cape Town, has collected a vast number of photographs dating from the Boer War in 1899 to date. He is comparing old photos with current ones taken at the same sites to document changes in the vegetation in southern Africa that can possibly be attributed to increased levels of CO2. Caution must be exercised though in relating bush encroachment primarily to global warming as many factors are responsible for changes in vegetation. For example, soils have a close association with which species of plants grows where and changes in the browsing factor of domestic livestock and wildlife impacts noticeably on the abundance of bush. The removal and absence of browsing animals, such as elephants, giraffe and goats, has had far reaching effects on the composition and structure of trees and shrubs in African savannas.

As mentioned earlier, there are the protagonists and the antagonists to global warming. Notably protagonists like Dr Phil Jones, from the Climate Change Research Unit at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom, the author Tim Flannery who wrote the “Weather makers” and the United States politician, Al Gore, who was involved in the DVD “An inconvenient truth”, are all convinced that global warming is a major threat to the world, unless co-coordinated steps are taken at a global level to act together and reduce emissions. On the other hand the antagonists and sceptics such as Bjorn Lomborg, Professor of statistics and researcher at the University of Aarhus in Denmark, author of the “Skeptical environmentalist” and Steve McIntyre, a Canadian mathematician, challenge the climate scientists’ integrity and believe that the changes in climate are part of long term climatic oscillations. While not being personally responsible, they set the stage for the publishing of the book the “Climate files” (Pierce, 2010) that details the acrimonious debate that developed between the two conflicting groups. Unfortunately, the debate has become highly politicised and personal as the sceptics are critical of the way in which environmental organisations make selective and misleading use of scientific evidence. Even the international panel of scientists known as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) involved in assessing the impacts of, and guiding the world on climate change challenges, has come under suspicion due to the sceptics. As a result, the climate change conference in Copenhagen in December 2009 was not the resounding success that it was anticipated to be and public scepticism about anthropogenic effects and their role in climate change has increased.

Assuming that anthropogenic factors are causing climate change then the main causes are burning fossil fuels associated with industry, generating electricity, airlines, automobiles and agriculture associated with land clearing for cropping and intensive livestock farming. It is also hypothesised that wildfires, especially the mega-fires currently occurring in different parts of the world, are caused by increased temperatures and drought conditions, resulting in significant contributions to global emissions. Current estimates are that 29,9 billion tons of CO2 emissions are being released into the atmosphere on a global scale, of these emissions 21,3 billion tons (71%) are from burning fossil fuels while 8,6 billion tons or 29% are from other sources. But unfortunately there is apparently no detailed, quantified information currently available on emissions from prescribed burning which is a key and often essential range management practice in wildlife conservation and domestic livestock production systems.

On the agricultural front the conversion of tropical forests (conservative global estimate of 21 000 km2 per year in 1989) (Molion, 1991) comprising mega-tons of standing biomass into cultivated areas for crop production with an average biomass of two to six tons, particularly in South America, Indonesia and parts of Central Africa, result in a significant net release of CO2 emissions into the atmosphere. However, cropping is not the main cause per se for increased emissions into the atmosphere because crop production results in a cyclic release and re-absorption of CO2 on a seasonal basis. It is rather the replacement of the mega-tons (biomass density of 300 metric tons per hectare) (Molion, 1991) of standing forest with a greatly reduced standing cropland vegetation (four to six tons per hectare) that are seen as the contribution of these activities to global warming.

In commercial beef production, especially feedlots with high concentrations of animals, there is a cyclic release of methane and nitrous oxide which is converted into CO2 but is eventually reabsorbed by forage production of maize and hay necessary to feed these animals. A similar situation occurs in the dairy industry, where the emissions attributed to increased numbers of milk cows, are re-absorbed by the highly productive and nutritious pastures that are grown to support these high forage demanding animals. Some food for thought though, is “what contribution does the increasing numbers of elephants in the Kruger National Park and other areas such as Botswana, together with the two million plus wildebeest that migrate annually on the Serengeti Plains, contribute to increased levels of methane in the atmosphere and thus global warming?”

Role of fire and prescribed burning in global emissions

Fire has been mankind’s companion and foe since the dawn of time. It is a fundamental element of the planet, like air, shaping the patterns of our lives. Peoples’ opinion of fire has changed often, but fire itself remains the same (de Golia, 1993). The real challenge is to understand it and the role it plays particularly in tropical grassland and savanna ecosystems. Fire is a natural factor of the environment and certain plants like some protea species in South Africa and plants with serotinous cones like pine trees are fire dependent. A fascinating example of fire dependence is Australian grass trees (Xanthorrhaea australis) that respond to ethylene gas released in the smoke during burning causing the initiation of flowering. Conversely there are plant species that are sensitive to and are destroyed by fire like Cliffortia paucistaminea (moist fynbos) in the Amathole Mountains in the Eastern Cape (Trollope, 1971). Both ecosystems however provide a range of benefits to society depending on the fire ecology of the area. It is important though to realise that the science of fire is not fully understood and is a highly complex phenomenon, similar to climate change.

In tropical savannas fires are considered a principle source of emissions to the atmosphere. However quantifying emissions from savanna fires is a highly complex process as the interplay of numerous factors, on both temporal and spatial scales can have either positive or negative effects. So whether fire can be classified as “green” – or not, is not a simple matter of conjecture or scientific calculation. Several factors affect the degree of emissions in a fire for example fuel composition, fuel curing, fire intensity and the degree of fuel combustion. Seasonality of the fires also contributes significantly to the amount and type of greenhouse gas emissions released during fires but information on the quantification of the different gases released during fires is not readily available particularly in Africa. Many fire ecologists are of the opinion that the reduction of emissions can be addressed by simply changing the seasonality of the fires from late season intense fires to early season cool fires (Trollope, 2010). However in the Dambo or ”mini-wetlands” of south western Zambia, early dry season fires actually produce more smoke emissions from incomplete combustion, even though the combustion factors are half as much (Hoffa et al, 1999). Therefore, at this stage it is only possible to draw general conclusions about fire and emissions until further highly technical research has provided the answers we are seeking.

Based on the fact that fire is a natural factor of the environment, it is important to differentiate between the effects of wildfires and prescribed fires. Society and governments demand more sophisticated fire suppression or prevention technologies without conceding that many rural societies depend on the traditional use of fire for their livelihoods. Policies and programs have often been designed around the belief that rural people are the cause of fire related problems whereas rural communities could in fact provide part of the solution. For example, in indigenous African paradigms, prescribed burning is generally conducted at the height of the dry season resulting in high intensity fires that control bush encroachment in contrast to scientifically based fire regimes that originally recommended low intensity fires after the spring rains in summer rainfall areas. Subsequent research disproved this latter practice confirming that the indigenous African paradigm was correct (Trollope, 2009). Intense, wild mega-fires, burning down forests, result in a net release of CO2, whereas the traditional use of fire as a means of maintaining productive habitats for livestock and forest products necessary for the survival of rural communities, involves the cyclic release of emissions. In the Okavango Delta in Botswana, tourism operators and tourists were of the opinion that the Okavango Delta, one of the largest remaining inland wetlands protected by the Ramsar Convention, was being negatively impacted by high intensity wildfires. Rural communities were blamed. An extensive investigation by Working on Fire International found the criticism to be unfounded and that such an ecosystem required fire for ecosystem health as long as the fires were not too intense or too frequent. For instance, papyrus burnt by a wildfire in the Permanent Swamps in January had regrown to a healthy stand of the same size within three months. The occurrence of wild life in the swamps such as frogs, insects, sitatunga and pythons, was also clear evidence of the resilience of this ecosystem and its dependence on fire (Trollope et al, 2006).

Fire is also responsible for promoting and maintaining grasslands at the expense of trees and shrubs (Trollope, 2007). Where fire and grazing are prevalent in higher rainfall areas like the rolling hills of the KwaZulu-Natal midlands, they are dominated by open, pyro-zootic grasslands. In contrast, where fire has been excluded in a protected area for 30 years, dense natural forest is developing (see figure 4).

Examples of the effects of global climate change

In spite of the scepticism about climate change like Bjorn Lomborg of “The Sceptical Environmentalist” fame, the general consensus of the main stream scientists involved in the global warming debate is that it is a major challenge for the world in the 21st century. Global temperatures are predicted by these scientists to rise 1,8 – 6,0oC by 2100. Mark Lynas, activist, journalist and author of the book Six Degrees, paints a chilling degree-by-degree scenario of the devastation likely to occur and issued a global warning – “Act now or risk mass extinction!” (Lynas, 2008). For many there is no doubt that global warming is occurring. This is borne out by the melting of glaciers the world over, rising sea levels threatening the Atoll nations and the disappearing ice caps both in the Arctic and Antarctic peninsulas. The plight of the polar bears with the melting pack ice highlighted the problem to the general public (Collins, 2007).

Closer to home, the major increase in bush encroachment in southern Africa, has been attributed to increased CO2 levels in the last century (Buitenwerf et al, 2011). This is supported by the hypothesis that C3 plants (trees and shrubs) are favoured by increased levels of CO2 compared to grasses which are C4 plants (C3 and C4 refer to the photosynthetic pathways involved in the metabolism of these plants). In this regard, Professor Tim Hofmann at the University of Cape Town, has collected a vast number of photographs dating from the Boer War in 1899 to date. He is comparing old photos with current ones taken at the same sites to document changes in the vegetation in southern Africa that can possibly be attributed to increased levels of CO2. Caution must be exercised though in relating bush encroachment primarily to global warming as many factors are responsible for changes in vegetation. For example, soils have a close association with which species of plants grows where and changes in the browsing factor of domestic livestock and wildlife impacts noticeably on the abundance of bush. The removal and absence of browsing animals, such as elephants, giraffe and goats, has had far reaching effects on the composition and structure of trees and shrubs in African savannas.

As mentioned earlier, there are the protagonists and the antagonists to global warming. Notably protagonists like Dr Phil Jones, from the Climate Change Research Unit at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom, the author Tim Flannery who wrote the “Weather makers” and the United States politician, Al Gore, who was involved in the DVD “An inconvenient truth”, are all convinced that global warming is a major threat to the world, unless co-coordinated steps are taken at a global level to act together and reduce emissions. On the other hand the antagonists and sceptics such as Bjorn Lomborg, Professor of statistics and researcher at the University of Aarhus in Denmark, author of the “Skeptical environmentalist” and Steve McIntyre, a Canadian mathematician, challenge the climate scientists’ integrity and believe that the changes in climate are part of long term climatic oscillations. While not being personally responsible, they set the stage for the publishing of the book the “Climate files” (Pierce, 2010) that details the acrimonious debate that developed between the two conflicting groups. Unfortunately, the debate has become highly politicised and personal as the sceptics are critical of the way in which environmental organisations make selective and misleading use of scientific evidence. Even the international panel of scientists known as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) involved in assessing the impacts of, and guiding the world on climate change challenges, has come under suspicion due to the sceptics. As a result, the climate change conference in Copenhagen in December 2009 was not the resounding success that it was anticipated to be and public scepticism about anthropogenic effects and their role in climate change has increased.

Assuming that anthropogenic factors are causing climate change then the main causes are burning fossil fuels associated with industry, generating electricity, airlines, automobiles and agriculture associated with land clearing for cropping and intensive livestock farming. It is also hypothesised that wildfires, especially the mega-fires currently occurring in different parts of the world, are caused by increased temperatures and drought conditions, resulting in significant contributions to global emissions. Current estimates are that 29,9 billion tons of CO2 emissions are being released into the atmosphere on a global scale, of these emissions 21,3 billion tons (71%) are from burning fossil fuels while 8,6 billion tons or 29% are from other sources. But unfortunately there is apparently no detailed, quantified information currently available on emissions from prescribed burning which is a key and often essential range management practice in wildlife conservation and domestic livestock production systems.

On the agricultural front the conversion of tropical forests (conservative global estimate of 21 000 km2 per year in 1989) (Molion, 1991) comprising mega-tons of standing biomass into cultivated areas for crop production with an average biomass of two to six tons, particularly in South America, Indonesia and parts of Central Africa, result in a significant net release of CO2 emissions into the atmosphere. However, cropping is not the main cause per se for increased emissions into the atmosphere because crop production results in a cyclic release and re-absorption of CO2 on a seasonal basis. It is rather the replacement of the mega-tons (biomass density of 300 metric tons per hectare) (Molion, 1991) of standing forest with a greatly reduced standing cropland vegetation (four to six tons per hectare) that are seen as the contribution of these activities to global warming.

In commercial beef production, especially feedlots with high concentrations of animals, there is a cyclic release of methane and nitrous oxide which is converted into CO2 but is eventually reabsorbed by forage production of maize and hay necessary to feed these animals. A similar situation occurs in the dairy industry, where the emissions attributed to increased numbers of milk cows, are re-absorbed by the highly productive and nutritious pastures that are grown to support these high forage demanding animals. Some food for thought though, is “what contribution does the increasing numbers of elephants in the Kruger National Park and other areas such as Botswana, together with the two million plus wildebeest that migrate annually on the Serengeti Plains, contribute to increased levels of methane in the atmosphere and thus global warming?”

Role of fire and prescribed burning in global emissions

Fire has been mankind’s companion and foe since the dawn of time. It is a fundamental element of the planet, like air, shaping the patterns of our lives. Peoples’ opinion of fire has changed often, but fire itself remains the same (de Golia, 1993). The real challenge is to understand it and the role it plays particularly in tropical grassland and savanna ecosystems. Fire is a natural factor of the environment and certain plants like some protea species in South Africa and plants with serotinous cones like pine trees are fire dependent. A fascinating example of fire dependence is Australian grass trees (Xanthorrhaea australis) that respond to ethylene gas released in the smoke during burning causing the initiation of flowering. Conversely there are plant species that are sensitive to and are destroyed by fire like Cliffortia paucistaminea (moist fynbos) in the Amathole Mountains in the Eastern Cape (Trollope, 1971). Both ecosystems however provide a range of benefits to society depending on the fire ecology of the area. It is important though to realise that the science of fire is not fully understood and is a highly complex phenomenon, similar to climate change.

In tropical savannas fires are considered a principle source of emissions to the atmosphere. However quantifying emissions from savanna fires is a highly complex process as the interplay of numerous factors, on both temporal and spatial scales can have either positive or negative effects. So whether fire can be classified as “green” – or not, is not a simple matter of conjecture or scientific calculation. Several factors affect the degree of emissions in a fire for example fuel composition, fuel curing, fire intensity and the degree of fuel combustion. Seasonality of the fires also contributes significantly to the amount and type of greenhouse gas emissions released during fires but information on the quantification of the different gases released during fires is not readily available particularly in Africa. Many fire ecologists are of the opinion that the reduction of emissions can be addressed by simply changing the seasonality of the fires from late season intense fires to early season cool fires (Trollope, 2010). However in the Dambo or ”mini-wetlands” of south western Zambia, early dry season fires actually produce more smoke emissions from incomplete combustion, even though the combustion factors are half as much (Hoffa et al, 1999). Therefore, at this stage it is only possible to draw general conclusions about fire and emissions until further highly technical research has provided the answers we are seeking.

Based on the fact that fire is a natural factor of the environment, it is important to differentiate between the effects of wildfires and prescribed fires. Society and governments demand more sophisticated fire suppression or prevention technologies without conceding that many rural societies depend on the traditional use of fire for their livelihoods. Policies and programs have often been designed around the belief that rural people are the cause of fire related problems whereas rural communities could in fact provide part of the solution. For example, in indigenous African paradigms, prescribed burning is generally conducted at the height of the dry season resulting in high intensity fires that control bush encroachment in contrast to scientifically based fire regimes that originally recommended low intensity fires after the spring rains in summer rainfall areas. Subsequent research disproved this latter practice confirming that the indigenous African paradigm was correct (Trollope, 2009). Intense, wild mega-fires, burning down forests, result in a net release of CO2, whereas the traditional use of fire as a means of maintaining productive habitats for livestock and forest products necessary for the survival of rural communities, involves the cyclic release of emissions. In the Okavango Delta in Botswana, tourism operators and tourists were of the opinion that the Okavango Delta, one of the largest remaining inland wetlands protected by the Ramsar Convention, was being negatively impacted by high intensity wildfires. Rural communities were blamed. An extensive investigation by Working on Fire International found the criticism to be unfounded and that such an ecosystem required fire for ecosystem health as long as the fires were not too intense or too frequent. For instance, papyrus burnt by a wildfire in the Permanent Swamps in January had regrown to a healthy stand of the same size within three months. The occurrence of wild life in the swamps such as frogs, insects, sitatunga and pythons, was also clear evidence of the resilience of this ecosystem and its dependence on fire (Trollope et al, 2006).

Fire is also responsible for promoting and maintaining grasslands at the expense of trees and shrubs (Trollope, 2007). Where fire and grazing are prevalent in higher rainfall areas like the rolling hills of the KwaZulu-Natal midlands, they are dominated by open, pyro-zootic grasslands. In contrast, where fire has been excluded in a protected area for 30 years, dense natural forest is developing (see figure 4).

Figure 4: The development of forest with protection from fire in moist grasslands of the KwaZulu -Natal Midlands

In the Kruger National Park, a comparison of the experimental burn plots in the Satara/Nwanedzi area highlights the role of fire in maintaining grasslands. A biennially burnt plot comprises open grassland whereas the adjacent control plot where fire has been excluded for 55 years has developed into tree dominated savanna community (see figure 5).

In the Kruger National Park, a comparison of the experimental burn plots in the Satara/Nwanedzi area highlights the role of fire in maintaining grasslands. A biennially burnt plot comprises open grassland whereas the adjacent control plot where fire has been excluded for 55 years has developed into tree dominated savanna community (see figure 5).

Figure 5: Contrasting effects of fire in the Kruger Nation National Park where biennial burning (left) maintains open grassland while the exclusion of fire has enabled the development of a tree dominated community (right).

In southern Georgia and parts of Florida in the USA fire is used as a tool for habitat management for bob white quail. Plantation owners/managers regularly burn the natural pine forests using cool fires to prevent the invasion of hardwood trees such as various species of oak, thus promoting an open understorey of grasses and forbs which are ideal habitat for the quail (see figure 6).

In southern Georgia and parts of Florida in the USA fire is used as a tool for habitat management for bob white quail. Plantation owners/managers regularly burn the natural pine forests using cool fires to prevent the invasion of hardwood trees such as various species of oak, thus promoting an open understorey of grasses and forbs which are ideal habitat for the quail (see figure 6).

Figure 6: Under-storey burning in longleaf pine forests in Georgia, USA, for bob white quail habitat

Ecologically acceptable reasons for burning veld/rangelands are to remove moribund or old unpalatable grass and to control and/or prevent encroachment of undesirable plants eg slangbos encroachment in the southern Free State. In the wild life sphere additional reasons for burning are to create and/or maintain the grass/tree balance, to attract wildlife to less preferred areas to minimise overutilisation of preferred areas and to maintain and/or create biodiversity. The recommended prescribed fire regime for sourveld or higher rainfall areas is, depending on the rainfall or the problem (bush encroachment or invasive species), a burning cycle of one to four years whereas sweetveld or arid areas, that is more sensitive to perturbations such as fire, require a cycle of burning every 10 to 20 years.

In answering the question posed in the introduction “Is fire green?” the general conclusions that can be drawn are that burning fossil fuels and the conversion of forests and woodlands into croplands, results in a net release of CO2 into the atmosphere. The physiological process of photosynthesis involves absorbing CO2 so the emissions from livestock are counter balanced by the growing of grain and fodder crops to feed them. Fire in savannas and grasslands result in the release of emissions but these are reabsorbed the following season by the regenerating rangelands during the subsequent growing season.

Ecologically acceptable reasons for burning veld/rangelands are to remove moribund or old unpalatable grass and to control and/or prevent encroachment of undesirable plants eg slangbos encroachment in the southern Free State. In the wild life sphere additional reasons for burning are to create and/or maintain the grass/tree balance, to attract wildlife to less preferred areas to minimise overutilisation of preferred areas and to maintain and/or create biodiversity. The recommended prescribed fire regime for sourveld or higher rainfall areas is, depending on the rainfall or the problem (bush encroachment or invasive species), a burning cycle of one to four years whereas sweetveld or arid areas, that is more sensitive to perturbations such as fire, require a cycle of burning every 10 to 20 years.

In answering the question posed in the introduction “Is fire green?” the general conclusions that can be drawn are that burning fossil fuels and the conversion of forests and woodlands into croplands, results in a net release of CO2 into the atmosphere. The physiological process of photosynthesis involves absorbing CO2 so the emissions from livestock are counter balanced by the growing of grain and fodder crops to feed them. Fire in savannas and grasslands result in the release of emissions but these are reabsorbed the following season by the regenerating rangelands during the subsequent growing season.

Quick navigation

Social

|

Who are we?FRI Media (Pty) Ltd is an independent publisher of technical magazines including the well-read and respected Fire and Rescue International, its weekly FRI Newsletter and the Disaster Management Journal. We also offer a complete marketing and publishing package, which include design, printing and corporate wear and gifts. |

Weekly FRI Newsletter |

© Copyright 2018 Fire and Rescue International. All Rights Reserved.