- Home

- Magazines

-

Newsletters

- 19 July 2024

- 12 July 2024

- 5 July 2024

- 28 June 2024

- 14 June 2024

- 7 June 2024

- 31 May 2024

- 24 May 2024

- 17 May 2024

- 10 May 2024

- 3 May 2024

- 26 April 2024

- 19 April 2024

- 12 April 2024

- 22 March 2024

- 15 March 2024

- 8 March 2024

- 1 March 2024

- 23 February 2024

- 16 February 2024

- 9 February 2024

- 26 January 2024

- 19 January 2024

- 12 January 2024

- 22 December 2023

- 1 December 2023

- 24 November 2023

- 10 November 2023

- 3 November 2023

- 27 October 2023

- 20 October 2023

- 13 October 2023

- 6 October 2023

- 29 September 2023

- 22 September 2023

- 15 September 2023

- 8 September 2023

- 25 August 2023

- 18 August 2023

- 11 August 2023

- 4 August 2023

- 28 July 2023

- 21 July 2023

- 14 July 2023

- 7 July 2023

- 30 June 2023

- 23 June 2023

- 15 June 2023

- 2 June 2023

- 26 May 2023

- 19 May 2023

- 12 May 2023

- 5 May 2023

- 28 April 2023

- 21 April 2023

- 14 April 2023

- 6 April 2023

- 31 March 2023

- 24 March 2023

- 17 March 2023

- 10 March 2023

- 3 March 2023

- 24 February 2023

- 17 February 2023

- 10 February 2023

- 3 February 2023

- 27 January 2023

- 13 January 2023

- 22 December 2022

- 15 December 2022

- 9 December 2022

- 2 December 2022

- 25 November 2022

- 18 November 2022

- 11 November 2022

- 4 November 2022

- Advertising

- Subscribe

- Articles

-

Galleries

- AOSH Firexpo 2024

- Midvaal Fit to Fight Fire 2024

- WoF KNP 2023 Gallery

- TFA 2023 Gallery

- DMISA Conference 2023

- ETS 2023 Gallery

- Drager Fire Combat and Rescue Challenge 2023

- AOSH Firexpo 2023

- Midvaal Fit to Fight Fire

- WC IFFD 2023

- NMU 13th Fire Management Symposium 2022

- JOIFF Africa Conference 2022

- ETS 2022 Gallery

- TFA 2022 Gallery

- IFFD 2018

- SAESI

- TFA

- WRC 2018

- WRC 2019

- A-OSH/Securex

- IFE AGM 2019

- ETS Ind Fire Comp Nov 2019

- ETS Challenge 2021

- Drager launch

- Drager Fire Combat and Rescue Challenge 2022

- TFA

- Contact

- Home

- Magazines

-

Newsletters

- 19 July 2024

- 12 July 2024

- 5 July 2024

- 28 June 2024

- 14 June 2024

- 7 June 2024

- 31 May 2024

- 24 May 2024

- 17 May 2024

- 10 May 2024

- 3 May 2024

- 26 April 2024

- 19 April 2024

- 12 April 2024

- 22 March 2024

- 15 March 2024

- 8 March 2024

- 1 March 2024

- 23 February 2024

- 16 February 2024

- 9 February 2024

- 26 January 2024

- 19 January 2024

- 12 January 2024

- 22 December 2023

- 1 December 2023

- 24 November 2023

- 10 November 2023

- 3 November 2023

- 27 October 2023

- 20 October 2023

- 13 October 2023

- 6 October 2023

- 29 September 2023

- 22 September 2023

- 15 September 2023

- 8 September 2023

- 25 August 2023

- 18 August 2023

- 11 August 2023

- 4 August 2023

- 28 July 2023

- 21 July 2023

- 14 July 2023

- 7 July 2023

- 30 June 2023

- 23 June 2023

- 15 June 2023

- 2 June 2023

- 26 May 2023

- 19 May 2023

- 12 May 2023

- 5 May 2023

- 28 April 2023

- 21 April 2023

- 14 April 2023

- 6 April 2023

- 31 March 2023

- 24 March 2023

- 17 March 2023

- 10 March 2023

- 3 March 2023

- 24 February 2023

- 17 February 2023

- 10 February 2023

- 3 February 2023

- 27 January 2023

- 13 January 2023

- 22 December 2022

- 15 December 2022

- 9 December 2022

- 2 December 2022

- 25 November 2022

- 18 November 2022

- 11 November 2022

- 4 November 2022

- Advertising

- Subscribe

- Articles

-

Galleries

- AOSH Firexpo 2024

- Midvaal Fit to Fight Fire 2024

- WoF KNP 2023 Gallery

- TFA 2023 Gallery

- DMISA Conference 2023

- ETS 2023 Gallery

- Drager Fire Combat and Rescue Challenge 2023

- AOSH Firexpo 2023

- Midvaal Fit to Fight Fire

- WC IFFD 2023

- NMU 13th Fire Management Symposium 2022

- JOIFF Africa Conference 2022

- ETS 2022 Gallery

- TFA 2022 Gallery

- IFFD 2018

- SAESI

- TFA

- WRC 2018

- WRC 2019

- A-OSH/Securex

- IFE AGM 2019

- ETS Ind Fire Comp Nov 2019

- ETS Challenge 2021

- Drager launch

- Drager Fire Combat and Rescue Challenge 2022

- TFA

- Contact

|

23 February 2024

|

Featured FRI Magazine article: Swift water rescue: A necessary special ops capacity in a changing world by Colin Deiner (FRI Vol 1 no 12)

https://www.frimedia.org/uploads/1/2/2/7/122743954/fri_vol1_no11_reduced.pdf

This week’s featured Fire and Rescue International magazine article is: Swift water rescue: A necessary special ops capacity in a changing world written by Colin Deiner, chief director, Disaster Management and Fire Brigade Services, Western Cape Provincial Government (FRI Vol 1 no 12). We will be sharing more technical/research/tactical articles from Fire and Rescue International magazine on a weekly basis with our readers to assist in technology transfer. This will hopefully create an increased awareness, providing you with hands-on advice and guidance. All our magazines are available free of charge in PDF format on our website and online at ISSUU. We also provide all technical articles as a free download in our article archive on our website.

Swift water rescue: A necessary special ops capacity in a changing world

By Colin Deiner, Chief Director, Disaster management and Fire Brigade Services, Western Cape Provincial Government

The continuing growth of informal settlements in and around South Africa’s cities and large towns have necessitated the emergency services of these areas to review and, in many cases drastically change, their methods of dealing with the many relatively new risks that face people living in these areas. We have had to adapt our fire trucks to move through very narrow pathways, modify our firefighting techniques to deal with structures that are virtually 100% flammable, we have to deal with a multitude of dwellings requiring search and rescue as well as aggressive firefighting at the same time and we have even had to develop new stretchers and rescue harnesses to remove people from various entrapment scenarios.

One of the biggest risks posed by these informal settlements is the fact that they are generally established around some sort of water source, in most cases a river. It is also a fact that the areas close to these rivers are considered prime sites for the erection of shacks and despite attempts by municipal authorities to remove people from these areas the difficulty in controlling the development within informal settlements leads to them always being inhabited. Emergency responders working in informal settlements situated close to rivers will tell you that they are generally confronted with the phenomenon of the river being a mere trickle in the dry season only to swell into a raging torrent during the rainy season. In certain parts of the country the dry season is also affected by wildland fires, which contribute to the dry riverbeds being filled with large heaps of tree branches, leaves and other types of biomass thereby clogging the waterway and causing the damming up of water during the early rains of the new season.

These “natural” dams can only hold a certain mass of water before bursting its banks and causing a flashflood downstream. Many eye witness accounts of people being swept away in informal settlements have indicated that people were walking through a specific path at one moment and at the next moment a huge stream of water appeared from “nowhere”. Of course, the illegal dumping of household waste is a contributor to this “damming” scenario.

A further, and more compound, hazard confronting inhabitants is what rescuers call “undercutting”. This occurs due to shacks sitting on the sides of deep rivers with no solid banks. As the water flows through the settlement on a continuous basis it erodes the sides of these banks to the point where it can no longer support the weight of the shacks and they collapse into the river, often taking a number of shacks and its inhabitants with it. More recently, we have also seen violent floods occur over roads in areas affected by poorly maintained drainage systems.

In painting the above picture I haven’t even mentioned the services that have to deal with the risk of sports and leisure activities on rivers in their towns and cities. A lazy Sunday afternoon of river rafting by a group of inexperienced people has often ended in tragedy. There is also the age old reality that alcohol only mixes with small amounts of water.

A swift water rescue team

The above risks are sadly the cause of a great many deaths in this county and dealing with them should become a priority for all emergency services with this risk in their areas of jurisdiction. The cut-back environment that emergency services currently operate in generally forces chiefs and managers to prioritise their budgets and focus on the more common types of incidents. A swift water rescue team carries a cost. Although your rescue kit might be relatively cheap (In comparison with a hydraulic rescue set for example) the major outlay will be for training. This is one field of rescue where you can’t use poorly trained responders. Training is also not readily available and only a small group of providers out there. Also most training courses have been derived from the river sports community and don’t specifically relate to the additional types of risks mentioned earlier in this article.

Swift water rescue technicians are strong swimmers who have a clear understanding of the dynamics of water flow and its related hazards. They must also be proficient at rope rescue systems and maintain a high degree of physical fitness and mental alertness. It is therefore obvious that not all responders will be able to achieve this. A junior fire fighter or ambulance attendant working in an informal settlement might spend most of his/her day responding to shack fires or ferrying patients to and from medical facilities and not see much need for swift water training. The problem is however that when the flashflood occurs they might be the first responders. They then need to know what to do and (most importantly), what not to do.

Swift water rescue training is divided into three levels. The first level is aimed at first responders and focuses mainly on land based rescues. The second level is the technician level and covers boat based rescues as well as physically entering the water and using rope systems. The third level is a specialist level and teaches the rescuer skills needed for handling personal watercraft and helicopter based rescues.

The table below gives a clearer indication of the requirements of the three levels

Training level

Requirements

First responders

Land based: Talk, flotation, reach, throw

Swift water rescue technician

Talk, flotation, reach, throw, row, go tow

Swift water specialist

All the above plus personal watercraft and helicopter based rescue

Low risk operations

A person trapped in rapidly flowing water has a very small window of survival and a rapid response is vital to ensure that survival. Entering water to rescue a person is an extremely high risk activity and should be the last option to be performed by a qualified, skilled and experienced rescue team. A number of low risk options exist which should be attempted first and can be performed by first responders:

As in any rescue scenario, pre-planning is vital. In many cases land-based, low-risk rescues may work at any point along the river. There will however be certain sites that may afford an optimum advantage and the best chance for a rescuer to conduct a successful rescue. A tour of the river bank by your rescue team will help to identify these sites and may also even provide strong points for you to establish pre-constructed anchor points on which to secure your ropes or rescuers performing shore based rescues.

Due to the fact that your swift water rescue teams are not as abundant as your first responders and may arrive well after them on a scene it is important to develop an interaction between the groups. The activities of the first responders can lengthen the window needed for a successful rescue downstream and give the victim a better chance of survival.

High risk operations

High risk operations are the types of activities that should only be performed by trained swift water rescue technicians. They include:

Constructing a highline across a river allows rescuers to work in higher flow velocities with a higher degree of control and lest physical exertion. These systems take a considerable amount of time to set up and it is very helpful to identify areas where they can be pre-rigged. Highlines have been deployed successfully to remove people from strainers, off vehicles and conducting low-head dam rescues.

The rescuer will then “tow” the victim to the shore by being upstream (behind) of the victim and guiding him/her to the shore.

The first scenario where helicopters can be effectively utilized is where a victim is floating in a river or stationary in a specific spot and a device is lowered to him/her. The victim would then attach themselves to the device and be raised up into the helicopter or placed down in a safe area into the hands of a medical crew for evaluation or treatment.

Victims can also be rescued by means of a tethered rescue pick-off which involves lowering a heli-based rescuer down to the victim. The rescuer will, upon reaching the victim, secure him/her to the haul line and be lifted out of the water.

Equipment

Equipment for swift water rescue is divided into personal protective gear or team rescue gear. Personal protective gear includes a wet suit (or dry suit), booties, gloves, a personal floatation device (PFD), a water rescue helmet, knife, whistle, strobe light, flashlight and swimming fins. Personal protective gear must be purpose made for water rescue and certified by a recognized authority. Using a standard rope rescue helmet in a swift water scenario can cause a serious neck injury if water shoots into the top of the helmet and has no openings through which to escape.

Team rescue equipment is dependent on the level of the rescue team and is made up of an assortment of ropes and related equipment, extra personal floatation devices and helmets, medical gear, throw bags, floatation rings, buoys, rescue boats, fluorescent lights and anchor rigging equipment.

Ideally all this equipment should be placed on a single four-wheel drive vehicle capable of responding quickly and negotiating difficult terrain along river banks.

Preparation, preparation, preparation

The secret to any successful rescue operation is preparation. You can never practice too much. Try to set a record for building a highline. Then try to improve on it every time you practice. Hold a competition for throw bag deployment. Let your team deploy rope from a bag and then retrieve it back into the bag in as short time as possible. These are the activities that can save you milliseconds during a rescue and improve your chances of saving a life.

Visit the rivers in your area. Identify the sites where you could set up. Practice deploying your team in those areas. It’s a lot more productive and fun than sitting in the station complaining about your chief or watching football re-runs on TV.

The third area to give attention is early warning. Recently a wide range of technology has become available whereby hazard areas can be identified by running software models over a geographic rendition of the river. This will guide you as to the kind of flooding you can expect with a certain rainfall intensity.

River sensors have been used with great success in the Jukskei River in Alexandra, Johannesburg during the nineties. These sensors alerted the Sandton Fire Department Swift water Rescue Team when the river reached a certain level and this prompted a response to a pre-determined area. Teams then used to monitor any upstream situations and be ready to rescue any person headed in their direction.

Ongoing theft of these components made it a difficult system to maintain. Recent improvements to the encasement of these systems should I believe be considered by services having similar risks.

Placement of your response units is most critical. Having your swift water team sitting at a station central to all your risks but impractically far away from them all is just stupid. Ideally you need one unit for each informal settlement with a major river flooding risk. A more specialized unit can be placed more centrally but may need to be moved into a high risk area if the indications are that a heavy downpour (with resultant flooding) might happen.

It will also be helpful to interact with agencies responsible for keeping rivers and channels clean and ensuring that all debris and bio-mass are removed prior to the wet season.

Remember, when a person’s head goes underwater you have less than a minute to act. Be prepared.

Responding to the incident

In the South African scenario it will generally be an initial response (low risk) unit that should arrive on scene first. There initial activities will include the following:

A safety officer should also be assigned during a swift water incident and it is this person’s prime responsibility to ensure that the general area surrounding the rescue site is safe. Bystanders should be evacuated from the site as well as any emergency service personnel not wearing the appropriate protective gear (firefighting/turnout gear has no place at a swift water incident and could prove disastrous to a fire fighter/rescuer accidentally falling into a river).

The safety officer should also ensure that no ropes are tied around rescuers bodies but rather to approved harnesses. A rope tied around a person’s body in moving water can cause serious injury and even death to a rescuer.

All activities must be coordinated with the incident commander and rescue squad leader to ensure maximum safety at all times.

The action plan

Once all information is analysed the incident commander should devise an action plan based on what is known as well as the team’s capabilities. Firstly consider all the low-risk options while setting up for high-risk options. Being ahead of the game is always advisable.

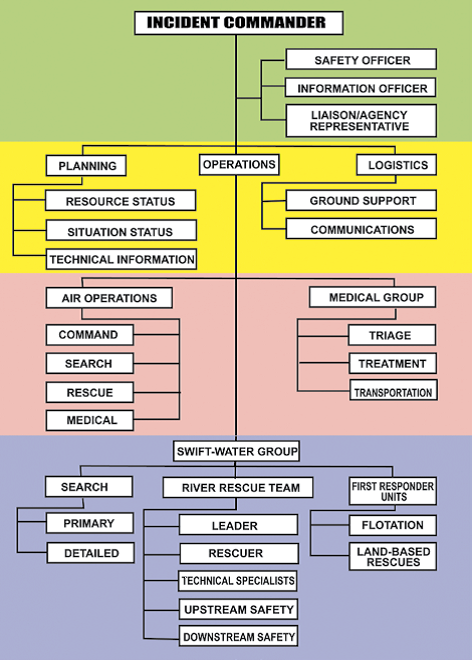

Any swift water incident will require the establishment of a strong incident command system which will vary in size depending on the magnitude of the incident. Figure 1 gives a good indication of an incident command structure during a major incident with multiple victims where air operations are a consideration.

Also keep in mind that rescuers entering the water may become affected by any number of evil contaminants and the need for decontamination must be a clear consideration.

The rescue team leader must at all times follow the action plan and direct all staff accordingly. He/she must communicate directly with incident command and provide status reports and requests for additional staff or equipment.

No plan will progress if it is not adequately critiqued after the incident. Spend time on this. It might lead to small tweaks in your procedures and provide more information on the prevailing river hazards in your region. Incorporate these changes into your plans and use them next time you have to respond.

Finally

Swift water rescue incidents have a nasty habit of turning rescuers into victims. It is only through a thorough process of establishing a good safety platform and working through low-risk to high-risk options that we can ensure that all our staff (and the victim) get to go home later. Let’s be careful out there on the river.

This week’s featured Fire and Rescue International magazine article is: Swift water rescue: A necessary special ops capacity in a changing world written by Colin Deiner, chief director, Disaster Management and Fire Brigade Services, Western Cape Provincial Government (FRI Vol 1 no 12). We will be sharing more technical/research/tactical articles from Fire and Rescue International magazine on a weekly basis with our readers to assist in technology transfer. This will hopefully create an increased awareness, providing you with hands-on advice and guidance. All our magazines are available free of charge in PDF format on our website and online at ISSUU. We also provide all technical articles as a free download in our article archive on our website.

Swift water rescue: A necessary special ops capacity in a changing world

By Colin Deiner, Chief Director, Disaster management and Fire Brigade Services, Western Cape Provincial Government

The continuing growth of informal settlements in and around South Africa’s cities and large towns have necessitated the emergency services of these areas to review and, in many cases drastically change, their methods of dealing with the many relatively new risks that face people living in these areas. We have had to adapt our fire trucks to move through very narrow pathways, modify our firefighting techniques to deal with structures that are virtually 100% flammable, we have to deal with a multitude of dwellings requiring search and rescue as well as aggressive firefighting at the same time and we have even had to develop new stretchers and rescue harnesses to remove people from various entrapment scenarios.

One of the biggest risks posed by these informal settlements is the fact that they are generally established around some sort of water source, in most cases a river. It is also a fact that the areas close to these rivers are considered prime sites for the erection of shacks and despite attempts by municipal authorities to remove people from these areas the difficulty in controlling the development within informal settlements leads to them always being inhabited. Emergency responders working in informal settlements situated close to rivers will tell you that they are generally confronted with the phenomenon of the river being a mere trickle in the dry season only to swell into a raging torrent during the rainy season. In certain parts of the country the dry season is also affected by wildland fires, which contribute to the dry riverbeds being filled with large heaps of tree branches, leaves and other types of biomass thereby clogging the waterway and causing the damming up of water during the early rains of the new season.

These “natural” dams can only hold a certain mass of water before bursting its banks and causing a flashflood downstream. Many eye witness accounts of people being swept away in informal settlements have indicated that people were walking through a specific path at one moment and at the next moment a huge stream of water appeared from “nowhere”. Of course, the illegal dumping of household waste is a contributor to this “damming” scenario.

A further, and more compound, hazard confronting inhabitants is what rescuers call “undercutting”. This occurs due to shacks sitting on the sides of deep rivers with no solid banks. As the water flows through the settlement on a continuous basis it erodes the sides of these banks to the point where it can no longer support the weight of the shacks and they collapse into the river, often taking a number of shacks and its inhabitants with it. More recently, we have also seen violent floods occur over roads in areas affected by poorly maintained drainage systems.

In painting the above picture I haven’t even mentioned the services that have to deal with the risk of sports and leisure activities on rivers in their towns and cities. A lazy Sunday afternoon of river rafting by a group of inexperienced people has often ended in tragedy. There is also the age old reality that alcohol only mixes with small amounts of water.

A swift water rescue team

The above risks are sadly the cause of a great many deaths in this county and dealing with them should become a priority for all emergency services with this risk in their areas of jurisdiction. The cut-back environment that emergency services currently operate in generally forces chiefs and managers to prioritise their budgets and focus on the more common types of incidents. A swift water rescue team carries a cost. Although your rescue kit might be relatively cheap (In comparison with a hydraulic rescue set for example) the major outlay will be for training. This is one field of rescue where you can’t use poorly trained responders. Training is also not readily available and only a small group of providers out there. Also most training courses have been derived from the river sports community and don’t specifically relate to the additional types of risks mentioned earlier in this article.

Swift water rescue technicians are strong swimmers who have a clear understanding of the dynamics of water flow and its related hazards. They must also be proficient at rope rescue systems and maintain a high degree of physical fitness and mental alertness. It is therefore obvious that not all responders will be able to achieve this. A junior fire fighter or ambulance attendant working in an informal settlement might spend most of his/her day responding to shack fires or ferrying patients to and from medical facilities and not see much need for swift water training. The problem is however that when the flashflood occurs they might be the first responders. They then need to know what to do and (most importantly), what not to do.

Swift water rescue training is divided into three levels. The first level is aimed at first responders and focuses mainly on land based rescues. The second level is the technician level and covers boat based rescues as well as physically entering the water and using rope systems. The third level is a specialist level and teaches the rescuer skills needed for handling personal watercraft and helicopter based rescues.

The table below gives a clearer indication of the requirements of the three levels

Training level

Requirements

First responders

Land based: Talk, flotation, reach, throw

Swift water rescue technician

Talk, flotation, reach, throw, row, go tow

Swift water specialist

All the above plus personal watercraft and helicopter based rescue

Low risk operations

A person trapped in rapidly flowing water has a very small window of survival and a rapid response is vital to ensure that survival. Entering water to rescue a person is an extremely high risk activity and should be the last option to be performed by a qualified, skilled and experienced rescue team. A number of low risk options exist which should be attempted first and can be performed by first responders:

- Talk: Assuming the victim is coherent and within shouting distance a series of instructions can be shouted in an attempt to manoeuvre him/her toward the riverbank where the rescuers are waiting. Once at the edge the victims can either exit the water themselves or be assisted by the rescuers.

- Flotation: This entails getting a flotation device to the victim and “buying time” for the rescue team to set up a more viable option. A flotation device such as a buoy or life vest should not only keep the victim afloat but also prevent the onset of hypothermia.

- Reach: Rescues are performed by extending lengthy equipment (such as a ceiling hook) to the victim who is within reach. If the victim can reach the equipment he/she can be can be pulled ashore and rescued from the water. Rescuers must be connected to a rope to prevent them from falling in the water themselves. This option must only be performed by trained personnel and is used mainly in stationary water where the victim is in contact with a stationary object.

- Throw: The throw bag is one of the most versatile pieces of equipment available, the quickest to deploy and can be used in a wide range of places. It has also been used in the most successful rescues. The throw bag usually contains a length of poly-propylene which floats on water and is highly visible to the victim. Rescuing a victim with a throw bag entails the rescuers tossing the bag in the path of the victim and then, after the victim has grabbed hold of the rope, pendulums him/her to the river bank.

As in any rescue scenario, pre-planning is vital. In many cases land-based, low-risk rescues may work at any point along the river. There will however be certain sites that may afford an optimum advantage and the best chance for a rescuer to conduct a successful rescue. A tour of the river bank by your rescue team will help to identify these sites and may also even provide strong points for you to establish pre-constructed anchor points on which to secure your ropes or rescuers performing shore based rescues.

Due to the fact that your swift water rescue teams are not as abundant as your first responders and may arrive well after them on a scene it is important to develop an interaction between the groups. The activities of the first responders can lengthen the window needed for a successful rescue downstream and give the victim a better chance of survival.

High risk operations

High risk operations are the types of activities that should only be performed by trained swift water rescue technicians. They include:

- Row: Here the rescuer enters the water in an inflatable boat or river rescue board, both of which are fitted with four secured handles. The handles of the boat are tethered and land-based rescuers on either sides of the river can then move the craft up- or downstream or from side to side until they are able to get it close enough to the victim for the boat-based rescuer to physically reach the victims or throw a line out to them. The most commonly used methods of deploying boats are the two- and four- point tethered systems. They are easy to set up but difficult to manage and do not always work well when there are obstacles along the river bank or in the river as a clear path is needed for the maneuvering of the ropes needed to control the boat movement.

Constructing a highline across a river allows rescuers to work in higher flow velocities with a higher degree of control and lest physical exertion. These systems take a considerable amount of time to set up and it is very helpful to identify areas where they can be pre-rigged. Highlines have been deployed successfully to remove people from strainers, off vehicles and conducting low-head dam rescues.

- Go and tow: This rescue involves the rescuer making physical contact with the victim who is usually unable to assist due to panic, injury or a compromised level on consciousness. A rescue swimmer will enter the water and aggressively make his/her way to the victim (approaching from upstream). When the victim is reached the swimmer will assume a defensive swimming position (on the back, facing downstream, feet in front) The rescuer is then able to control the movement of himself and the victim. In most (if not all) cases the victim will not have the same level of protection that the rescuer has and therefore the rescuer must be prepared for any unsuspected or sudden movements from the victim.

The rescuer will then “tow” the victim to the shore by being upstream (behind) of the victim and guiding him/her to the shore.

- Helicopter: A helicopter based rescue requires a skilled pilot and crew that have trained together and understand the highly technical challenges of a heli-based rescue operation. This option should be seen as a last resort as it presents a range of hazards such as power lines, bridges, etc.

The first scenario where helicopters can be effectively utilized is where a victim is floating in a river or stationary in a specific spot and a device is lowered to him/her. The victim would then attach themselves to the device and be raised up into the helicopter or placed down in a safe area into the hands of a medical crew for evaluation or treatment.

Victims can also be rescued by means of a tethered rescue pick-off which involves lowering a heli-based rescuer down to the victim. The rescuer will, upon reaching the victim, secure him/her to the haul line and be lifted out of the water.

- Personal watercraft: Personal watercrafts such as hovercrafts or small inboard boats are extremely versatile and can generally be deployed at any point in a river. The major disadvantage of these types of craft is the costs thereof.

Equipment

Equipment for swift water rescue is divided into personal protective gear or team rescue gear. Personal protective gear includes a wet suit (or dry suit), booties, gloves, a personal floatation device (PFD), a water rescue helmet, knife, whistle, strobe light, flashlight and swimming fins. Personal protective gear must be purpose made for water rescue and certified by a recognized authority. Using a standard rope rescue helmet in a swift water scenario can cause a serious neck injury if water shoots into the top of the helmet and has no openings through which to escape.

Team rescue equipment is dependent on the level of the rescue team and is made up of an assortment of ropes and related equipment, extra personal floatation devices and helmets, medical gear, throw bags, floatation rings, buoys, rescue boats, fluorescent lights and anchor rigging equipment.

Ideally all this equipment should be placed on a single four-wheel drive vehicle capable of responding quickly and negotiating difficult terrain along river banks.

Preparation, preparation, preparation

The secret to any successful rescue operation is preparation. You can never practice too much. Try to set a record for building a highline. Then try to improve on it every time you practice. Hold a competition for throw bag deployment. Let your team deploy rope from a bag and then retrieve it back into the bag in as short time as possible. These are the activities that can save you milliseconds during a rescue and improve your chances of saving a life.

Visit the rivers in your area. Identify the sites where you could set up. Practice deploying your team in those areas. It’s a lot more productive and fun than sitting in the station complaining about your chief or watching football re-runs on TV.

The third area to give attention is early warning. Recently a wide range of technology has become available whereby hazard areas can be identified by running software models over a geographic rendition of the river. This will guide you as to the kind of flooding you can expect with a certain rainfall intensity.

River sensors have been used with great success in the Jukskei River in Alexandra, Johannesburg during the nineties. These sensors alerted the Sandton Fire Department Swift water Rescue Team when the river reached a certain level and this prompted a response to a pre-determined area. Teams then used to monitor any upstream situations and be ready to rescue any person headed in their direction.

Ongoing theft of these components made it a difficult system to maintain. Recent improvements to the encasement of these systems should I believe be considered by services having similar risks.

Placement of your response units is most critical. Having your swift water team sitting at a station central to all your risks but impractically far away from them all is just stupid. Ideally you need one unit for each informal settlement with a major river flooding risk. A more specialized unit can be placed more centrally but may need to be moved into a high risk area if the indications are that a heavy downpour (with resultant flooding) might happen.

It will also be helpful to interact with agencies responsible for keeping rivers and channels clean and ensuring that all debris and bio-mass are removed prior to the wet season.

Remember, when a person’s head goes underwater you have less than a minute to act. Be prepared.

Responding to the incident

In the South African scenario it will generally be an initial response (low risk) unit that should arrive on scene first. There initial activities will include the following:

- Gather information: The first-in unit should identify any witnesses and gather all relevant information. Firstly they should try to determine if there were in fact any victims (and how many). They should also try to gather the following information:

- The time of the incident;

- The location at which the victim/s were last seen;

- A description of the victim/s; and

- Rivers involved.

- Identify hazards: Safety is always the priority and hazards such as debris, fences, bridges, trees/bushes, hydraulics, low-head dams, hydroelectric power plants and multiple channels should be identified.

A safety officer should also be assigned during a swift water incident and it is this person’s prime responsibility to ensure that the general area surrounding the rescue site is safe. Bystanders should be evacuated from the site as well as any emergency service personnel not wearing the appropriate protective gear (firefighting/turnout gear has no place at a swift water incident and could prove disastrous to a fire fighter/rescuer accidentally falling into a river).

The safety officer should also ensure that no ropes are tied around rescuers bodies but rather to approved harnesses. A rope tied around a person’s body in moving water can cause serious injury and even death to a rescuer.

All activities must be coordinated with the incident commander and rescue squad leader to ensure maximum safety at all times.

The action plan

Once all information is analysed the incident commander should devise an action plan based on what is known as well as the team’s capabilities. Firstly consider all the low-risk options while setting up for high-risk options. Being ahead of the game is always advisable.

Any swift water incident will require the establishment of a strong incident command system which will vary in size depending on the magnitude of the incident. Figure 1 gives a good indication of an incident command structure during a major incident with multiple victims where air operations are a consideration.

Also keep in mind that rescuers entering the water may become affected by any number of evil contaminants and the need for decontamination must be a clear consideration.

The rescue team leader must at all times follow the action plan and direct all staff accordingly. He/she must communicate directly with incident command and provide status reports and requests for additional staff or equipment.

No plan will progress if it is not adequately critiqued after the incident. Spend time on this. It might lead to small tweaks in your procedures and provide more information on the prevailing river hazards in your region. Incorporate these changes into your plans and use them next time you have to respond.

Finally

Swift water rescue incidents have a nasty habit of turning rescuers into victims. It is only through a thorough process of establishing a good safety platform and working through low-risk to high-risk options that we can ensure that all our staff (and the victim) get to go home later. Let’s be careful out there on the river.

Quick navigation

Social

|

Who are we?FRI Media (Pty) Ltd is an independent publisher of technical magazines including the well-read and respected Fire and Rescue International, its weekly FRI Newsletter and the Disaster Management Journal. We also offer a complete marketing and publishing package, which include design, printing and corporate wear and gifts. |

Weekly FRI Newsletter |

© Copyright 2018 Fire and Rescue International. All Rights Reserved.