- Home

- Magazines

-

Newsletters

- 19 July 2024

- 12 July 2024

- 5 July 2024

- 28 June 2024

- 14 June 2024

- 7 June 2024

- 31 May 2024

- 24 May 2024

- 17 May 2024

- 10 May 2024

- 3 May 2024

- 26 April 2024

- 19 April 2024

- 12 April 2024

- 22 March 2024

- 15 March 2024

- 8 March 2024

- 1 March 2024

- 23 February 2024

- 16 February 2024

- 9 February 2024

- 26 January 2024

- 19 January 2024

- 12 January 2024

- 22 December 2023

- 1 December 2023

- 24 November 2023

- 10 November 2023

- 3 November 2023

- 27 October 2023

- 20 October 2023

- 13 October 2023

- 6 October 2023

- 29 September 2023

- 22 September 2023

- 15 September 2023

- 8 September 2023

- 25 August 2023

- 18 August 2023

- 11 August 2023

- 4 August 2023

- 28 July 2023

- 21 July 2023

- 14 July 2023

- 7 July 2023

- 30 June 2023

- 23 June 2023

- 15 June 2023

- 2 June 2023

- 26 May 2023

- 19 May 2023

- 12 May 2023

- 5 May 2023

- 28 April 2023

- 21 April 2023

- 14 April 2023

- 6 April 2023

- 31 March 2023

- 24 March 2023

- 17 March 2023

- 10 March 2023

- 3 March 2023

- 24 February 2023

- 17 February 2023

- 10 February 2023

- 3 February 2023

- 27 January 2023

- 13 January 2023

- 22 December 2022

- 15 December 2022

- 9 December 2022

- 2 December 2022

- 25 November 2022

- 18 November 2022

- 11 November 2022

- 4 November 2022

- Advertising

- Subscribe

- Articles

-

Galleries

- AOSH Firexpo 2024

- Midvaal Fit to Fight Fire 2024

- WoF KNP 2023 Gallery

- TFA 2023 Gallery

- DMISA Conference 2023

- ETS 2023 Gallery

- Drager Fire Combat and Rescue Challenge 2023

- AOSH Firexpo 2023

- Midvaal Fit to Fight Fire

- WC IFFD 2023

- NMU 13th Fire Management Symposium 2022

- JOIFF Africa Conference 2022

- ETS 2022 Gallery

- TFA 2022 Gallery

- IFFD 2018

- SAESI

- TFA

- WRC 2018

- WRC 2019

- A-OSH/Securex

- IFE AGM 2019

- ETS Ind Fire Comp Nov 2019

- ETS Challenge 2021

- Drager launch

- Drager Fire Combat and Rescue Challenge 2022

- TFA

- Contact

- Home

- Magazines

-

Newsletters

- 19 July 2024

- 12 July 2024

- 5 July 2024

- 28 June 2024

- 14 June 2024

- 7 June 2024

- 31 May 2024

- 24 May 2024

- 17 May 2024

- 10 May 2024

- 3 May 2024

- 26 April 2024

- 19 April 2024

- 12 April 2024

- 22 March 2024

- 15 March 2024

- 8 March 2024

- 1 March 2024

- 23 February 2024

- 16 February 2024

- 9 February 2024

- 26 January 2024

- 19 January 2024

- 12 January 2024

- 22 December 2023

- 1 December 2023

- 24 November 2023

- 10 November 2023

- 3 November 2023

- 27 October 2023

- 20 October 2023

- 13 October 2023

- 6 October 2023

- 29 September 2023

- 22 September 2023

- 15 September 2023

- 8 September 2023

- 25 August 2023

- 18 August 2023

- 11 August 2023

- 4 August 2023

- 28 July 2023

- 21 July 2023

- 14 July 2023

- 7 July 2023

- 30 June 2023

- 23 June 2023

- 15 June 2023

- 2 June 2023

- 26 May 2023

- 19 May 2023

- 12 May 2023

- 5 May 2023

- 28 April 2023

- 21 April 2023

- 14 April 2023

- 6 April 2023

- 31 March 2023

- 24 March 2023

- 17 March 2023

- 10 March 2023

- 3 March 2023

- 24 February 2023

- 17 February 2023

- 10 February 2023

- 3 February 2023

- 27 January 2023

- 13 January 2023

- 22 December 2022

- 15 December 2022

- 9 December 2022

- 2 December 2022

- 25 November 2022

- 18 November 2022

- 11 November 2022

- 4 November 2022

- Advertising

- Subscribe

- Articles

-

Galleries

- AOSH Firexpo 2024

- Midvaal Fit to Fight Fire 2024

- WoF KNP 2023 Gallery

- TFA 2023 Gallery

- DMISA Conference 2023

- ETS 2023 Gallery

- Drager Fire Combat and Rescue Challenge 2023

- AOSH Firexpo 2023

- Midvaal Fit to Fight Fire

- WC IFFD 2023

- NMU 13th Fire Management Symposium 2022

- JOIFF Africa Conference 2022

- ETS 2022 Gallery

- TFA 2022 Gallery

- IFFD 2018

- SAESI

- TFA

- WRC 2018

- WRC 2019

- A-OSH/Securex

- IFE AGM 2019

- ETS Ind Fire Comp Nov 2019

- ETS Challenge 2021

- Drager launch

- Drager Fire Combat and Rescue Challenge 2022

- TFA

- Contact

|

22 December 2023

|

Featured FRI Magazine article: Ventilation: tactical objective or afterthought written by Colin Deiner (FRI Vol 1 no 10)

https://www.frimedia.org/uploads/1/2/2/7/122743954/vol1no10_lr_final.pdf

This week’s featured Fire and Rescue International magazine article is: Ventilation: tactical objective or afterthought written by Colin Deiner, chief director, Disaster management and Fire Brigade Services, Western Cape Provincial Government (FRI Vol 1 no 10). We will be sharing more technical/research/tactical articles from Fire and Rescue International magazine on a weekly basis with our readers to assist in technology transfer. This will hopefully create an increased awareness, providing you with hands-on advice and guidance. All our magazines are available free of charge in PDF format on our website and online at ISSUU. We also provide all technical articles as a free download in our article archive on our website.

Ventilation: tactical objective or afterthought

By Colin Deiner, chief director, Disaster management and Fire Brigade Services, Western Cape Provincial Government

“One of the major reasons that fires get out of control is the lack of proper and adequate ventilation. If you want to move in on a smoky fire, you must ventilate or you will be driven out. Yes, you can and should use masks to hold difficult positions. However, most jobs (fires) will be readily controlled by good, fast ventilation and a crew determined to move in” (Fried, 1972).

The measure of our success when dealing with a structural fire can be measured in one of two ways: (1) did we stop the fire at the point we found it when we arrived?, or (2) did we set up a point where we could attack a fast moving fire and effectively extinguish the fire from that point?

The first criteria will be used when responding to a structural fire that generally will be confined to the room and contents of the occupancy and can typically be extinguished by means of a rapid interior attack that is well supported by effective forcible entry and ventilation. The second criteria will be used when responding to a thatch roof or strip mall type fire that has already spread into the ceiling and will require a fair amount of hose deployment and setting up of equipment before the actual fire attack can begin. The incident commander should decide on a specific point from which this set-up can be done safely and from where the fire can be controlled.

In both of the above situations, a number of peripheral activities that should form part of the initial operation must support the fire attack. Hose teams must be able to gain safe entry into the structure and a forcible entry capacity must be in place from the get-go. The ability of the team to move and work in a specific direction within the building and extinguish the fire with the least amount of collateral damage will be largely dependent on the effectiveness of the ventilation that supports the fire attack. There are certain signs that I always look out for when making up my mind as to how good the fire service is that I am being shown (like the layout of the equipment in the kit bunkers). One of the most important of these is the ability to move smoke as effectively as they can move water.

Most fire services will have a well-developed standard operating procedure for aggressive fire attack that will include all the actions needed to support at least three hose teams as part of their initial attack. It is, however, the first arriving incident commander who must have the ability to recognise the risk facing him/her and immediately take advantage of the possible favourable conditions that present themselves. A quick and effective fire attack is dependent on a quick and effective set-up of equipment. This can only be achieved through a whole lot of practice. This practice must be done almost daily until it becomes second nature on every call. As an operations officer, in another lifetime, I established a practice where at least three lines had to be pulled on every structural fire my service attended. This had to be supported by a positive pressure ventilation deployment as well as good forcible entry capability. In most cases, we didn’t need it at all and I used to get a lot of really dirty looks from fire fighters having to roll up and clean unused fire hose, but we never struggled to initiate a rapid interior attack when we needed to. We saved a lot of property this way, and a few lives.

So what is ventilation?

For those of us who grew up in the fire services of the 80s and 90s, we will believe the definition of ventilation to be ““the systematic removal of heat, smoke, and fire gases, and replacing them with cooler air”. This is true, although only partly. Actually, the definition of ventilation would be more correct if it said something about the exchange of the atmosphere inside a building to that of the outside. It also does not always include smoke, heat and gasses. In effect, what we are doing is replacing the bad atmosphere (on the inside) with fresh air (from the outside) which includes that critical component of the fire triangle….OXYGEN. OK, so how do we do this without harming our fire fighters or burning the building down any further?

Ventilation as a tactical objective can be implemented for any of the following three reasons:

Another good fire-spread prevention practice which was developed in the mid-nineties (specifically to deal with fires in houses with heavy tile roof construction), is for the roof attack team to access the ceiling void and apply class-A foam into the unburned area. This will in most cases protect the roof trusses from too much direct flame impingement and allow it to maintain its integrity for a while longer.

Neither of the above two practices fall within the definition of “ventilation” but are mentioned here because they both require the very much the same actions to be achieved as the more pure ventilation practices.

Ventilation as a tactical tool

The obvious risk presented by the application of a ventilation strategy is that while we are attempting to remove the hazardous products of fire from within a confined area, we are allowing fresh air to fill the vacuum caused by the removal of the smoke. This alters the dynamics of the fire by increasing the amount of oxygen being provided to it and will increase the size of the fire we are dealing with. We therefore need to be clear in our minds as to what the impact of the intended ventilation activity will have on the overall strategy and success of the operation. Some of the things we need to consider are:

The incident commander must take all these possibilities into account and the impact of these possible changes in the fire/smoke pattern must be allowed for in the overall action plan. The early and effective set-up of resources will be the most critical indicator of the success or failure of the operation.

Ventilation can be done in a variety of ways and the method to be used will generally be dictated by the type and condition of the structure, severity and size of the fire column, possibility of rescue and capabilities of equipment and staff. Creating a ventilation opening in the direction the smoke is travelling does seem to make the most sense but may not always be possible. Vertical ventilation practices are very popular in the United States and most of the literature we get from there does focus largely on this. In South Africa, however, we do not always have the kind of roof construction that is conducive to vertical ventilation and a better option would be to employ a horizontal ventilation strategy designed to force the smoke in a pre-determined direction.

Natural ventilation

The traditional method of ventilation (natural ventilation) which allows for the entry of air through the windward side of the building and out through the leeward side is achieved by opening or removing the structure’s “natural openings“ such as windows and doors and letting nature take its course. This method will, however, always be dictated by the direction and force of the prevailing wind conditions and this in itself will limit the options of the incident commander.

Forced ventilation

A number of fire services will also use smoke ejectors (or fans) to supplement natural ventilation when they are not achieving their objectives through natural ventilation. Ejectors are not able to move the volume of smoke as effectively as natural ventilation or forced ventilation but do offer a number of options when ventilation of confined spaces is required.

They are also good boosters for positive pressure tactics in large volume structures and can be effective in stairwell ventilation when used in conjunction with positive pressure tactics as well.

The placement of ejectors might create challenges, as you will need to mount them as close as possible to the heat and smoke. This will require hanging them from a door frame or mounting them high in the vent opening. This can be done by placing ladders on either side of the opening, using ladder rungs or hanging the ejector on fan jacks placed on the inside of the door frame. This might impede the egress route of fire victims. You must also ensure that you are not recycling the smoke and heat products back into the structure or pushing any combustion products into other congested spaces. This can be achieved by closing the spaces around the ejector housing. If possible, the open space around the fan housing should be sealed and a clear airflow path should be established.

Vertical ventilation

Vertical ventilation is generally considered to be the most difficult and hazardous task on the fireground and needs to be done with a high level of safety. The type of roof construction will obviously dictate the type of opening that can be created and the effectiveness that can be achieved. By committing fire fighters to the roof of a burning structure, we are not only putting them in the way of the fire but we are also placing them on top of structural elements that may already have been severely weakened. We therefore need to afford them the necessary protection and this can be achieved by making sure of the following three things:

Laddering: Ladders should be used to provide quick and safe access to the roof, safer footing for any pitched roof and to spread the load imposed by the fire fighters performing the task. You need good ladders and you need a lot of them. Take some time to have a look at the number and type of ladders sitting on your fire truck parked in the engine bay. Can you provide access for your ventilation crew (three people) and a hose team (two more people)? Do you have sufficient roof ladders for them all to be on secure footing, and are you able to provide two avenues of escape? In a previous article in this magazine, I alluded to the necessity for a ladder truck or “ladder tender” to be included as a first response resource to any working structural fire. This is one of the main motivations why it should. Remember, there is a reason that NFPA specifications require eleven ground ladders on a ladder truck.

Cutting equipment: Improvements in ventilation saws over the last 20 years have made this job significantly safer and easier and cut down on the time that crews have to be exposed to the inherent risks of vertical ventilation. Higher capacity saws and the use of the “bullet” chain fitted onto a specially designed chainsaw, provides a longer cutting reach as well as affording a high level of protection to the operator. Two unique features of these saws are the depth gauge that allows the operator to pre-set the part of the cutting chain that will be exposed. This ensures that, in the event of an accident, fire fighters will only be at the minimum risk of a moving chainsaw. The other “neat” feature is the filter that allows the chain to operate in a smoke filled environment. When you are making an opening above a fire, you are going to be in a smoke filled cloud very soon. You do not want to have your saw pack up on you before you finish your cut. It is for the above reason that you must insist that your procurement department purchases these specialised cutters. A standard cutter will generally not have these features and this will compromise the safety of your staff.

The minimum equipment that the ventilation crew working on a roof should have includes a powered saw (chain or circular), an axe to lift the decking after the cut (and in case the saw breaks down) and a pike pole/ceiling hook for breaking through the ceiling.

Hose line: It is not easy lugging a hose line up a roof and finding a safe place for two fire fighters to be “at-the-ready” but it is an absolute necessity. A lot of research has been done around the optimal hose line diameter for aggressive interior fire fighting and I’m sure different people will have differing opinions. I have found in the South African context that the 45mm hose gives you good mobility as well as sufficient knockdown capacity. Considering that most of the jobs you will be doing will be single family residential fires, you would want to limit the extent of the water damage as much as you can. When the lounge sofa comes floating out of the front door, you need to urgently relook your tactics.

A few final thoughts on vertical ventilation

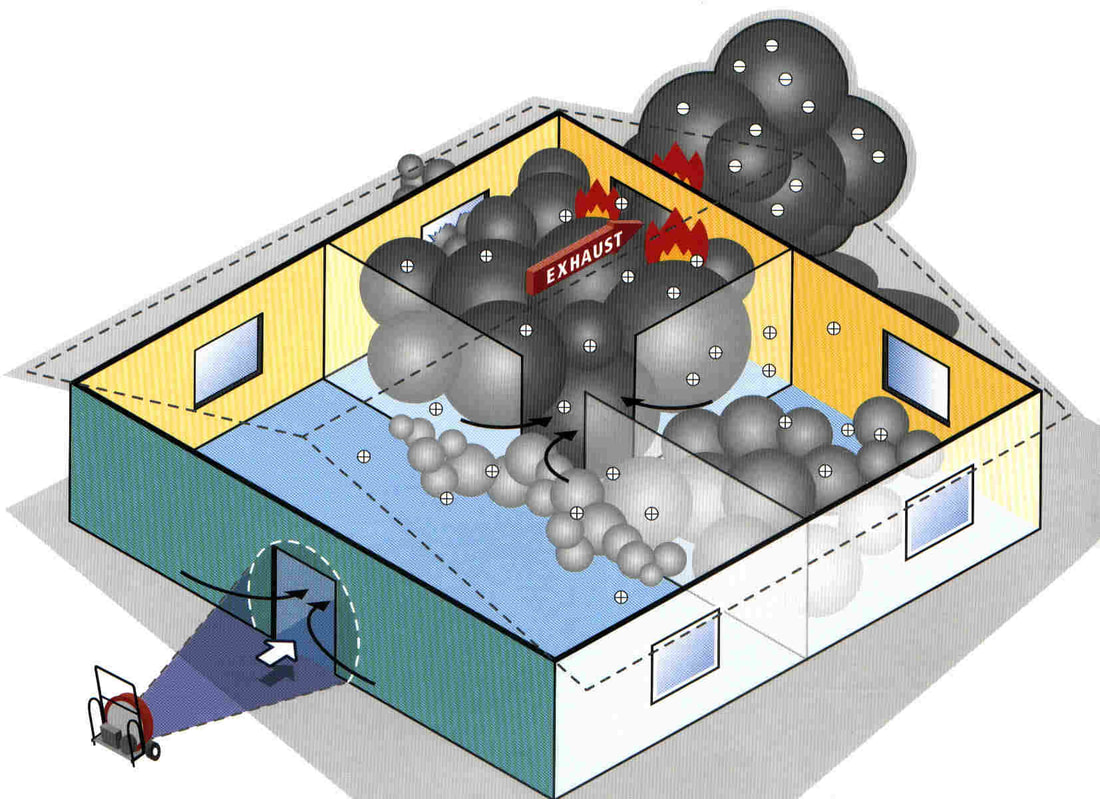

Positive pressure ventilation (PPV)

PPV has become the primary method of ventilation for many fire services in the last twenty years. PPV is designed to support a rapid fire attack and the main objective is to use a high volume fan (blower) to create an area of positive pressure inside a building and in so doing, force the smoke and heat to move to an area of lower pressure outside the building. It has many advantages, the most important being the ability to quickly change the atmosphere in a structure to a survivable one. The second (for me) most important advantage is that it allows the incident commander to dictate the direction in which he/she would like to channel the smoke and heat. It is critical though, that there be only one entrance for the ventilation unit and only one exit for the removal of smoke and heat. This exit must be smaller than the opening or there will be no build-up of positive pressure.

PPV does however also have a major disadvantage and that is that it can cause a rapid increase in fire development. It is critical, for this reason, that all entry hose teams are ready to enter the structure before the PPV blowers. The ventilation opening should be placed between the hose team and the fire or between the fire and trapped victims. It is vital to know where the fire is and where it is going to move once the operation starts.

Many factors will dictate the success of a PPV strategy. A few to keep in mind are:

Hydro ventilation

This type of ventilation is simple yet very effective and involves the use of water streams to expel smoke and heat from a structure. Making use of the Venturi Principle, the hose crew will direct their fog stream towards an open window and in so doing cause the hydraulic effect of the fog stream to create a vacuum and move the surrounding smoke out of the structure at a relatively high velocity. The most effective use of the fog ventilation works when the stream is positioned so the fog pattern covers most of the window opening. The nozzle should be about a half-metre from the window frame and should be in a wide fog pattern.

Hydro ventilation is a short-term ventilation tactic that has been designed to provide a quick advantage to the entry teams before a more sustainable ventilation strategy is implemented.

Conclusion

I hope that this article will once again get you thinking about the way you approach your response to single dwelling structural fires specifically. When we tell people that we have an aggressive approach to attacking structural fires, are we also able to tell them how to support this approach? Any aggressive interior attack can only work if all the parts of the system are working in concert with each other. Keep it simple and ensure that every crew working in the various fire zones are kept updated on the prevailing situation. You had better be doing everything right when everything goes wrong.

Remember when they say ―”Somebody do something” you’re the somebody they’re talking about.

This week’s featured Fire and Rescue International magazine article is: Ventilation: tactical objective or afterthought written by Colin Deiner, chief director, Disaster management and Fire Brigade Services, Western Cape Provincial Government (FRI Vol 1 no 10). We will be sharing more technical/research/tactical articles from Fire and Rescue International magazine on a weekly basis with our readers to assist in technology transfer. This will hopefully create an increased awareness, providing you with hands-on advice and guidance. All our magazines are available free of charge in PDF format on our website and online at ISSUU. We also provide all technical articles as a free download in our article archive on our website.

Ventilation: tactical objective or afterthought

By Colin Deiner, chief director, Disaster management and Fire Brigade Services, Western Cape Provincial Government

“One of the major reasons that fires get out of control is the lack of proper and adequate ventilation. If you want to move in on a smoky fire, you must ventilate or you will be driven out. Yes, you can and should use masks to hold difficult positions. However, most jobs (fires) will be readily controlled by good, fast ventilation and a crew determined to move in” (Fried, 1972).

The measure of our success when dealing with a structural fire can be measured in one of two ways: (1) did we stop the fire at the point we found it when we arrived?, or (2) did we set up a point where we could attack a fast moving fire and effectively extinguish the fire from that point?

The first criteria will be used when responding to a structural fire that generally will be confined to the room and contents of the occupancy and can typically be extinguished by means of a rapid interior attack that is well supported by effective forcible entry and ventilation. The second criteria will be used when responding to a thatch roof or strip mall type fire that has already spread into the ceiling and will require a fair amount of hose deployment and setting up of equipment before the actual fire attack can begin. The incident commander should decide on a specific point from which this set-up can be done safely and from where the fire can be controlled.

In both of the above situations, a number of peripheral activities that should form part of the initial operation must support the fire attack. Hose teams must be able to gain safe entry into the structure and a forcible entry capacity must be in place from the get-go. The ability of the team to move and work in a specific direction within the building and extinguish the fire with the least amount of collateral damage will be largely dependent on the effectiveness of the ventilation that supports the fire attack. There are certain signs that I always look out for when making up my mind as to how good the fire service is that I am being shown (like the layout of the equipment in the kit bunkers). One of the most important of these is the ability to move smoke as effectively as they can move water.

Most fire services will have a well-developed standard operating procedure for aggressive fire attack that will include all the actions needed to support at least three hose teams as part of their initial attack. It is, however, the first arriving incident commander who must have the ability to recognise the risk facing him/her and immediately take advantage of the possible favourable conditions that present themselves. A quick and effective fire attack is dependent on a quick and effective set-up of equipment. This can only be achieved through a whole lot of practice. This practice must be done almost daily until it becomes second nature on every call. As an operations officer, in another lifetime, I established a practice where at least three lines had to be pulled on every structural fire my service attended. This had to be supported by a positive pressure ventilation deployment as well as good forcible entry capability. In most cases, we didn’t need it at all and I used to get a lot of really dirty looks from fire fighters having to roll up and clean unused fire hose, but we never struggled to initiate a rapid interior attack when we needed to. We saved a lot of property this way, and a few lives.

So what is ventilation?

For those of us who grew up in the fire services of the 80s and 90s, we will believe the definition of ventilation to be ““the systematic removal of heat, smoke, and fire gases, and replacing them with cooler air”. This is true, although only partly. Actually, the definition of ventilation would be more correct if it said something about the exchange of the atmosphere inside a building to that of the outside. It also does not always include smoke, heat and gasses. In effect, what we are doing is replacing the bad atmosphere (on the inside) with fresh air (from the outside) which includes that critical component of the fire triangle….OXYGEN. OK, so how do we do this without harming our fire fighters or burning the building down any further?

Ventilation as a tactical objective can be implemented for any of the following three reasons:

- Rescue

- Fire fighting

- Preventing the spread of fire

Another good fire-spread prevention practice which was developed in the mid-nineties (specifically to deal with fires in houses with heavy tile roof construction), is for the roof attack team to access the ceiling void and apply class-A foam into the unburned area. This will in most cases protect the roof trusses from too much direct flame impingement and allow it to maintain its integrity for a while longer.

Neither of the above two practices fall within the definition of “ventilation” but are mentioned here because they both require the very much the same actions to be achieved as the more pure ventilation practices.

Ventilation as a tactical tool

The obvious risk presented by the application of a ventilation strategy is that while we are attempting to remove the hazardous products of fire from within a confined area, we are allowing fresh air to fill the vacuum caused by the removal of the smoke. This alters the dynamics of the fire by increasing the amount of oxygen being provided to it and will increase the size of the fire we are dealing with. We therefore need to be clear in our minds as to what the impact of the intended ventilation activity will have on the overall strategy and success of the operation. Some of the things we need to consider are:

- Will the ventilation cause the heat and smoke onto the fire victims and/or fire crews?

- What will the impact of the ventilation have on the egress paths of victims or fire fighters?

- Will the ventilation create a backdraft or a flashover?

- Are hose teams in position to deal with sudden change in fire conditions?

The incident commander must take all these possibilities into account and the impact of these possible changes in the fire/smoke pattern must be allowed for in the overall action plan. The early and effective set-up of resources will be the most critical indicator of the success or failure of the operation.

Ventilation can be done in a variety of ways and the method to be used will generally be dictated by the type and condition of the structure, severity and size of the fire column, possibility of rescue and capabilities of equipment and staff. Creating a ventilation opening in the direction the smoke is travelling does seem to make the most sense but may not always be possible. Vertical ventilation practices are very popular in the United States and most of the literature we get from there does focus largely on this. In South Africa, however, we do not always have the kind of roof construction that is conducive to vertical ventilation and a better option would be to employ a horizontal ventilation strategy designed to force the smoke in a pre-determined direction.

Natural ventilation

The traditional method of ventilation (natural ventilation) which allows for the entry of air through the windward side of the building and out through the leeward side is achieved by opening or removing the structure’s “natural openings“ such as windows and doors and letting nature take its course. This method will, however, always be dictated by the direction and force of the prevailing wind conditions and this in itself will limit the options of the incident commander.

Forced ventilation

A number of fire services will also use smoke ejectors (or fans) to supplement natural ventilation when they are not achieving their objectives through natural ventilation. Ejectors are not able to move the volume of smoke as effectively as natural ventilation or forced ventilation but do offer a number of options when ventilation of confined spaces is required.

They are also good boosters for positive pressure tactics in large volume structures and can be effective in stairwell ventilation when used in conjunction with positive pressure tactics as well.

The placement of ejectors might create challenges, as you will need to mount them as close as possible to the heat and smoke. This will require hanging them from a door frame or mounting them high in the vent opening. This can be done by placing ladders on either side of the opening, using ladder rungs or hanging the ejector on fan jacks placed on the inside of the door frame. This might impede the egress route of fire victims. You must also ensure that you are not recycling the smoke and heat products back into the structure or pushing any combustion products into other congested spaces. This can be achieved by closing the spaces around the ejector housing. If possible, the open space around the fan housing should be sealed and a clear airflow path should be established.

Vertical ventilation

Vertical ventilation is generally considered to be the most difficult and hazardous task on the fireground and needs to be done with a high level of safety. The type of roof construction will obviously dictate the type of opening that can be created and the effectiveness that can be achieved. By committing fire fighters to the roof of a burning structure, we are not only putting them in the way of the fire but we are also placing them on top of structural elements that may already have been severely weakened. We therefore need to afford them the necessary protection and this can be achieved by making sure of the following three things:

Laddering: Ladders should be used to provide quick and safe access to the roof, safer footing for any pitched roof and to spread the load imposed by the fire fighters performing the task. You need good ladders and you need a lot of them. Take some time to have a look at the number and type of ladders sitting on your fire truck parked in the engine bay. Can you provide access for your ventilation crew (three people) and a hose team (two more people)? Do you have sufficient roof ladders for them all to be on secure footing, and are you able to provide two avenues of escape? In a previous article in this magazine, I alluded to the necessity for a ladder truck or “ladder tender” to be included as a first response resource to any working structural fire. This is one of the main motivations why it should. Remember, there is a reason that NFPA specifications require eleven ground ladders on a ladder truck.

Cutting equipment: Improvements in ventilation saws over the last 20 years have made this job significantly safer and easier and cut down on the time that crews have to be exposed to the inherent risks of vertical ventilation. Higher capacity saws and the use of the “bullet” chain fitted onto a specially designed chainsaw, provides a longer cutting reach as well as affording a high level of protection to the operator. Two unique features of these saws are the depth gauge that allows the operator to pre-set the part of the cutting chain that will be exposed. This ensures that, in the event of an accident, fire fighters will only be at the minimum risk of a moving chainsaw. The other “neat” feature is the filter that allows the chain to operate in a smoke filled environment. When you are making an opening above a fire, you are going to be in a smoke filled cloud very soon. You do not want to have your saw pack up on you before you finish your cut. It is for the above reason that you must insist that your procurement department purchases these specialised cutters. A standard cutter will generally not have these features and this will compromise the safety of your staff.

The minimum equipment that the ventilation crew working on a roof should have includes a powered saw (chain or circular), an axe to lift the decking after the cut (and in case the saw breaks down) and a pike pole/ceiling hook for breaking through the ceiling.

Hose line: It is not easy lugging a hose line up a roof and finding a safe place for two fire fighters to be “at-the-ready” but it is an absolute necessity. A lot of research has been done around the optimal hose line diameter for aggressive interior fire fighting and I’m sure different people will have differing opinions. I have found in the South African context that the 45mm hose gives you good mobility as well as sufficient knockdown capacity. Considering that most of the jobs you will be doing will be single family residential fires, you would want to limit the extent of the water damage as much as you can. When the lounge sofa comes floating out of the front door, you need to urgently relook your tactics.

A few final thoughts on vertical ventilation

- Beware the underfoot conditions. The notion that everyone on the fireground is a safety officer is seldom as relevant as here. All crews working on the roof must check for tell-tale signs of roof failure or deterioration in the fire conditions. If you see the roof sagging, bubbling or smoke and heating pouring out of it, you have a sure sign that the roofs integrity has been compromised.

- Incident command should be on top of all activities on the fireground and must ensure that the interior crews are totally prepared for the change in conditions after the ventilation opening has been made. Failure to do so will guarantee both crews discussing their opinions on the others maternal relations after the fire.

Positive pressure ventilation (PPV)

PPV has become the primary method of ventilation for many fire services in the last twenty years. PPV is designed to support a rapid fire attack and the main objective is to use a high volume fan (blower) to create an area of positive pressure inside a building and in so doing, force the smoke and heat to move to an area of lower pressure outside the building. It has many advantages, the most important being the ability to quickly change the atmosphere in a structure to a survivable one. The second (for me) most important advantage is that it allows the incident commander to dictate the direction in which he/she would like to channel the smoke and heat. It is critical though, that there be only one entrance for the ventilation unit and only one exit for the removal of smoke and heat. This exit must be smaller than the opening or there will be no build-up of positive pressure.

PPV does however also have a major disadvantage and that is that it can cause a rapid increase in fire development. It is critical, for this reason, that all entry hose teams are ready to enter the structure before the PPV blowers. The ventilation opening should be placed between the hose team and the fire or between the fire and trapped victims. It is vital to know where the fire is and where it is going to move once the operation starts.

Many factors will dictate the success of a PPV strategy. A few to keep in mind are:

- The cone of air coming from the blower must seal off the entrance. Make sure it is placed far enough away from the opening to achieve this. A single fan should be placed between 1,8 and 3 metres from the opening. The best way to make sure this is happening is to have someone stand at the opening during the set-up phase and test the quality of the seal.

- Hose teams must move into the building within the first 15 to 30 seconds of the blower starting. If you have too much of a delay, the fire will intensify.

- Ensure that you have sufficient blowers and that they are effective immediately. If you are not seeing results at an early stage you might want to move the first blower forward and place a second blower behind the first to seal of the entrance. The first blower should then be between 1 and 1,5 metres from the opening.

- You can also place blowers side by side to cover the opening of an oversized or double door.

- Ensure that the blowers have been set up in a clean environment that won’t affect the running of their fuel powered engines. The carbon monoxide emissions from your motor must also not be blown through the fan. This could cause the blower to quit or, at worse, introduce more carbon monoxide into an area with victims already struggling to survive.

- Always wear your breathing apparatus. Tests have shown PPV to be extremely successful in expelling toxic vapours from within a burning structure but there may still be hazardous vapours of various densities present that could kill you.

Hydro ventilation

This type of ventilation is simple yet very effective and involves the use of water streams to expel smoke and heat from a structure. Making use of the Venturi Principle, the hose crew will direct their fog stream towards an open window and in so doing cause the hydraulic effect of the fog stream to create a vacuum and move the surrounding smoke out of the structure at a relatively high velocity. The most effective use of the fog ventilation works when the stream is positioned so the fog pattern covers most of the window opening. The nozzle should be about a half-metre from the window frame and should be in a wide fog pattern.

Hydro ventilation is a short-term ventilation tactic that has been designed to provide a quick advantage to the entry teams before a more sustainable ventilation strategy is implemented.

Conclusion

I hope that this article will once again get you thinking about the way you approach your response to single dwelling structural fires specifically. When we tell people that we have an aggressive approach to attacking structural fires, are we also able to tell them how to support this approach? Any aggressive interior attack can only work if all the parts of the system are working in concert with each other. Keep it simple and ensure that every crew working in the various fire zones are kept updated on the prevailing situation. You had better be doing everything right when everything goes wrong.

Remember when they say ―”Somebody do something” you’re the somebody they’re talking about.

Quick navigation

Social

|

Who are we?FRI Media (Pty) Ltd is an independent publisher of technical magazines including the well-read and respected Fire and Rescue International, its weekly FRI Newsletter and the Disaster Management Journal. We also offer a complete marketing and publishing package, which include design, printing and corporate wear and gifts. |

Weekly FRI Newsletter |

© Copyright 2018 Fire and Rescue International. All Rights Reserved.